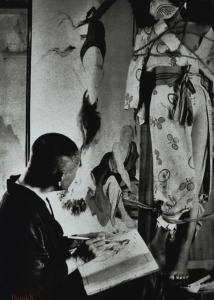

Recently, I had the opportunity to discuss rope with Chiba Eizo while visiting him in Tokyo. Our discussion eventually turned to the paintings of Itoh Seiu, one of the earliest and certainly the best known of the 20th century seme-e (torture pictures) painters.

What is missing in so much of the later art, Chiba sensei argued, was the feeling of Urami. It is a difficult concept to understand outside of the Japanese context. The word itself implies a grudge or feeling of resentment, such as something a son might feel toward his enemy who has killed his father. It is a common theme in Japanese ghost stories as well. The feeling that has brought the ghost into the world, seeking revenge against one who has wrong him or her, can be described as the feeling of urami.

At a deeper cultural level, urami comes from the “Shinto/Buddhist idea where the soul is bound to Earth by unfulfilled desires. These desires can be anything—unrequited love, unexpressed gratitude, unfinished business” (Davisson).

The theme occurs frequently in kabuki theater and, as a theater critic and scholar, Itoh would have a deep understanding of the concept. Urami has not only a feeling of anger or resentment to it, but also has a remarkable sense of beauty.

The theme occurs frequently in kabuki theater and, as a theater critic and scholar, Itoh would have a deep understanding of the concept. Urami has not only a feeling of anger or resentment to it, but also has a remarkable sense of beauty.

As I started to explore the concept in more detail, another side emerged which I think related even more deeply to the concept of rope. Urami plays upon the concept of “ura” or the hidden or inside. In contrast to the idea of “omote” which means outside, surface of face, “ura” refers to that which is kept hidden. The concept of division between the public and the private is an essential Japanese cultural concept. The things that are kept hidden, the private world of the mind is called “omoi,” which Kuno Akira explains accordingly:

“Omoi” means “thoughts”, “feelings” , “affections”, “emotions”, “desire” and so forth, but this word implies that the subject of these mental processes keeps them to himself, and does not expose them outside. ” (Kuno Akira, 1991)

Here we can start to understand the importance of urami in the art of Itoh and others as well as how rope and seme can function to bring those sorts of feelings to the surface. The rope scene itself sets the context for these feelings of resentment or a grudge. The complexity and beauty of rope is in its power to release these feelings, to open up the “Omoi” and give it space for expression.

In Kabuki theater, the job of the actor is to make the “Omoi” known without the use of words. As Kuno explains, “in the posturing called “Omoi-ire”, a Kabuki actor gives expression to the Omoi, without resort to language, only with the look on his face and the movement of his body.” Such a description could aptly describe a rope scene as well.

This too is the power of rope, the space for the person who is tied to reveal “omoi” to bring the thoughts, feelings, and emotions from the private hidden place, the space of Ura, to the surface and to allow them to be displayed. Being in rope, becomes an “Omoi-ire,” an expression of those hidden feelings and expressions that can not be exposed any other way.

The power of rope, the essence of the drama of a good rope scene, is rooted in this sense of Urami. Unlike a Kabuki play, which may be a tale of revenge or like the ghost story which recalls a spirit to the world to settle a grudge, the Urami of the rope scene can give rise to feelings and emotions that otherwise might have to remain hidden. Urami in this case is not anger or resentment directed at the person doing the tying, but rather, it is a struggle which allows the personal and private to come out into the open. Kuno concludes his discussion of Urami in Kabuki by exploring a similar dynamic when he writes:

Thus the Urami is not a direct reaction against maltreatment at all, but there it arises where such a reaction is impossible for some reason or other. . . .persuaded neither of external things nor of one’s own perception, one turns one’s eyes from the outer world to one’s own interior, and the Urami becomes connected with one’s being. (1991)

When admiring the work of Itoh, or later artists such as Kita Reiko (who Chiba sensei also singled out as a master of Urami), we can begin to understand one aspect of the drama of rope.

When we speak of “connection” in rope, I can think of no more beautiful or more sacred connection that someone opening themselves to show that which they hide from the world on a daily basis. To witness the overcoming and release of the struggle, the resentment, and the grudge of everyday life and to share them in that moment; there can be no greater connection.

Works Cited:

Kuno Akira, The Structure of “Urami,” Japan Review, 1991, 2: 117-123

Zack Davisson, “The History of Hausu“