In working with Sunohara san, I have had an amazing opportunity to review 30 videos of Nureki Chimuo’s kinbiken workshops from the 1980s and 1990s. These are remarkable documents not so much for the techniques that are shown as much as for the context they reveal about how rope evolved, particularly in Tokyo, during that period.

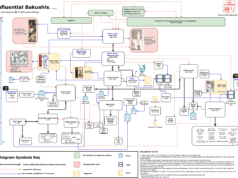

Of all the bakushi in the history of kinbaku, Nureki seems to be the most overlooked in the west, particularly in relation to the importance he holds in the history and evolution of modern kinbaku.

Nureki emerged in the rope scene in Tokyo working with Minomura Kou, one of the early bakushi, editors, and artists of the burgeoning post war rope scene in Tokyo. After a brief association with Kitan Club in Osaka, Minomura moved to Tokyo and began a series of publications that would include Uramado, which Nureki would later go on to edit.

The style of rope that emerged around Minomura was radically different from other styles of rope that were taking hold in Japan. As opposed to the flashier styles of Tsuijumra, Osada Eikichi, and Akechi Denki, those in Minomura’s circle were less concerned with stage and performance and more grounded personal and private play. In addition to Nureki, that circle included Yukimura Haruki, novelist Oniroku Dan, film rigger Urado Hiroshi, and many other luminaries of the kinbaku world.

This is the context in which Kinbiken emerged. Nureki was known for using models who were not professionals or AV actresses, but who were, instead, generally masochistic enthusiasts. In other words, women who loved rope in their personal lives, but would were not active as part of the adult video industry.

The focus of Kinbiken was always to bring out the beauty of the model, rather than to focus on the beauty of the rope. Techniques often varied dramatically from meeting to meeting, but within each video you always see a progression. It was always Nureki’s challenge to find the element of intensity or suffering that the model could provide.

The name itself, Kinbiken, is a contraction of Kinbakubi kenkyūkai, or Beautiful Bondage Study Group. The focus on Kinbaku-bi, the aesthetics of kinbaku, makes Kinbiken different from most rope study groups or dojos.

Kinbaku-bi is a difficult concept to nail down. It varies from person to person, both in how they tie and in how they view the ties they see. A core difference, however, seems to focus on where we look. For some, it is the rope itself. For others it is the expression of emotion, feeling, and communication which makes rope beautiful. For some it is both, or perhaps the intersection of the two.

What I find moving and powerful about Nureki’s rope is not his technical ability, which is stunning in its own right. It is his ability to draw out and evoke the emotions of the women he ties. Each video is a masterclass in finding what I would call the deep aesthetics of kinbaku, looking past the tie itself to find some deeper meaning and experience in the act of tying and being tied. Later in life, Nureki would call this “serious rope,” in contrast to the work he often did for hire in videos or for magazines.

In many ways, the work of those who followed Akechi Denki’s style of rope have dominated most of what gets taught in the west (Naka Akira’s ryuu being a notable exception). Artists like Osada Steve, Kinoko Hajime, Nawashi Kanna, and Kazami Ranki have played a central role in bringing kinbaku to the west. Their aesthetic is born from a different context and set of concerns.

The Akechi style differs from the Minomura style in two important respects. The first is technical. The techniques of Minomura’s followers tend to be more minimalist in design and less focused on performance-based suspension and dynamic transitions. The other aspect, which I would content is more important, is one of aesthetics.

While the aesthetics of the stage show dominate the Akechi lineage, the Minomura approach focuses on the aesthetic of the woman. What is beautiful is not the rope itself, but what it reveals in the woman who is tied.

To that end, the rope matters less than the effect it achieves. Nowhere is this more clear than in the videos of Nureki’s kinbiken.

I have often felt that in the west we have been cursed by an influx of technique, especially in the past few years, where we can learn the technical aspects of ties in a few short hours. What we are missing is the context that define what those ties mean and how they function to create a connection between the person tying and the one being tied.

That context developed gradually over decades in Japan, which makes it hard to explain or teach to those outside of it. The things that are understood and assumed comprise a significant portion of the meaning of kinbaku.

Without that context, it becomes harder and harder to find the deep meaning of kinbaku, to find kinbaku-bi.

It it something that cannot be taught, but it can be demonstrated. Opening the vaults to Nureki’s vision of beautiful bondage has been, for me, a step in the direction of building my own context for creating beautiful bondage that transcends the rope and the tie and speaks to the heart and spirit of kinbaku.

Nureki’s Kinbiken videos are currently avaailable at Japanese Bound