During my recent trip to Japan, I was struck by a recurring theme. In four separate conversations with some of the older rope artists in Japan, each spoke of how difficult it was when they first started out to find partners to tie. When Chiba Eizo started tying, he told me, it was almost impossible to bring the topic up with your partner as it was considered to be “extremely perverted.” For decades even professional bakushi had difficulty finding models to tie.

One person even speculated that one of the reasons Nureki and Akechi got so good at rope was that they had access to more bottoms than anyone else. They got to practice all the time, so they were able to improve quickly in their technique. Finding women to tie was extremely challenging and kinbaku was something that was very much “underground” and the desires attached to were considered “abnormal” by most.

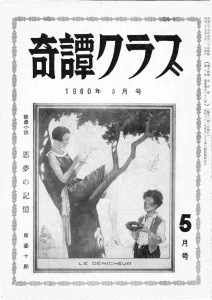

If you look back to the time when rope was becoming more visible in Japan, after the war, it is a time marked by a lot of turmoil and social conflict. Not unlike the US, Japan was wrestling with concepts of public morality and decency. In the 1950s, there were obscenity trials related to SM, including having one of the most famous SM magazines, Kitan Club, shut down for most of 1955 after their April issue was seized by the government.

During the “White Cover Period” (白表紙時代) of Kitan Club, which SMPedia defines as 1955 – 1967, the magazine only had 4 main models. While other models show up in smaller roles or as subjects of photos for sale, only four women are consistently active as models over this 12 year period. For more than a decade, the most famous rope magazine in Japan featured only four main models, and if you include others, the grand total of women in Kitan Club for that time period only expands to about three dozen.

During the “White Cover Period” (白表紙時代) of Kitan Club, which SMPedia defines as 1955 – 1967, the magazine only had 4 main models. While other models show up in smaller roles or as subjects of photos for sale, only four women are consistently active as models over this 12 year period. For more than a decade, the most famous rope magazine in Japan featured only four main models, and if you include others, the grand total of women in Kitan Club for that time period only expands to about three dozen.

This is also the period where may of the first generation of Japanese bakushi were growing up and first becoming exposed to rope bondage. Most of them, when asked, would also point to those magazines as a primary reference for learning how to tie.

The result of this activity being both underground and difficult to engage in has resulted in, what I believe, is a culture of rope. I mean that in the broadest sense. There is a significant history that has led to a shared set of values and beliefs around kinbaku in Japan that operates tacitly. A lot of that was probably absorbed through the stories and content that filled the magazines of the day as well.

Having a rope culture means that there is a complex context for rope that is well and deeply understood by those who practice it, usually learned through participation and observation over a long period of time. Cultural understandings are things you know but may not be able to articulate. They guide your actions and perceptions, without ever being made explicit.

Kinbaku as a Culture of Appreciation

The rope culture of Japan, I believe, is rooted in and still reflects the history from which it emerged. It is a culture that I would describe as one of appreciation. By that I mean that there is a certain amount of respect afforded not only to those who practice rope, either a tops or bottoms, but an appreciation for the opportunity to engage in kinbaku at all. To this day, it colors how many see rope and how they manage their relationships with other rope tops and, more importantly, with their rope bottoms.

The point I want to make is that because of its long tradition and history, kinbaku in Japan has developed a sense of culture, which is fundamental to understanding it as a practice.

In Japan (or at least in Tokyo, which is the only kinbaku in Japan I have any sense of) there is also a rope community. The community, or more properly communities, because they are always multiple, is where differences in practice, philosophies, and values get worked out. Not everyone likes each other. There are clubs, events, meetings, rope salons, and classes. But all of these things operate in the broader culture of rope in Japan, which is a shared understanding and context of what kinbaku is and how it fits into the larger world.

If we contrast this to the US and Europe, there is a significant difference.

In the West, kinbaku is a relatively recent phenomenon. Arguably, it hasn’t really been a significant part of the western SM world until the past decade or so. There hasn’t been much time to develop a culture of rope and what has passed as rope culture has usually been borrowed from Japan.

When we have been able to develop in the west is a sense of community. That community has really grown and blossomed in the past few years. For a decade, there was only a single rope conference in the US and only a slightly longer history of kinbaku in Europe. But recently, rope events have exploded in number, each expanding our sense of community. The number of classes alone in most areas has made kinbaku accessible in a way it have has been before, even in Japan. Our communities are based on these shared experiences and practices.

Kinbaku East and West

The difference between Japan and the west, is that technique in the west was able to develop practically overnight. Our communities developed almost exclusively as communities of learning and practice, without an underlying culture of appreciation. Compared to Japan where you were mostly likely learning from magazines and lucky if you could ever find a partner willing to even be tied, the west has an overabundance of learning opportunities without the stigma of perversion that made finding bottoms next to impossible.

I believe there is a culture of kinbaku in west that is developing, but the way it is taking shape is fundamentally different from what happened in Japan.

Because in the west, we have never faced shortages of partners, struggles of censorship and indecency, or the need to develop technique, we haven’t seen our culture develop in the same way. We have had our kinbaku technique handed to us after 50 or 60 years of development and as a result the skills that took decades to develop in Japan are now being transmitted in weekend workshops.

The level of skill in the west is on par with Japan, even according to many of the top Japanese bakushi, and that happened almost overnight.

The flow of development between Japan and the west is exactly reversed however. In Japan, technique developed over a long period of time as the result of an emerging culture of kinbaku. Culture gave birth to technique. In the west, technique has come first and has developed rapidly over a very short period of time, with a nascent culture growing up around it. Instead of the practice of kinbaku emerging from culture (as is the case in Japan) in the west we have a culture emerging from the practice of kinbaku. Technique is giving birth to culture.

Rope Culture in the West

So what does this emerging culture of kinbaku look like in the west?

First and foremost, it is technique based and is defined by people and names as much as by the actual style of rope itself. We describe ties based on who rather than what. Naka Akira’s takate kote, as opposed to say, Kinoko Hajime’s takate kote.

Second, how we regard those who tie in the west is also based on technique. In some cases because they can transmit particular knowledge from Japan, often from having visited and studied there, other times because they are able to do more complicated, beautiful, extreme, or painful rope. For some, pictures on Fetlife’s Kinky & Popular can lead to praise, popularity, teaching opportunities, and increasing numbers of bottoms willing to be tied by them.

Third, many tend to value rope bottoms based on their ability to handle difficult, challenging, or painful ties. There is even an emerging culture where some bottoms workout and train to be able to last longer in ties or be able to hold a more beautiful pose. Bottoms are often chosen to match technique, as opposed to adapting techniques to rope partners.

Fourth, we are a suspension culture. For most in the west, suspension is seen both as a higher level of difficulty than other forms of tying and the most visually dramatic and impressive kind of tying. For many it is also a validation of skill. It also affords the ability for those who tie to experiment with new, increasingly complicated ties. Improvements in techniques are often geared toward making suspensions safer or more comfortable to extend their duration.

Fifth, we are becoming a culture where ties are “performed” in the sense that we believe they should be done a particular way, look a particular way, and create a particular effect. When ties are taught, the “why” of the tie is usually based on effect, not affect. How a tie “feels” is usually a question of sensation, rather than emotion.

Finally, rope in the west, for a lot of people, has become a test of skill, both for tops and bottoms. The closest analogy I can think of is something like a culture of extreme sport. Innovation in kinbaku is analogous to snowboarders learning their next trick. In the same way, if your trick gets popular enough, you even get to put your name on it.

Our communities may define what we do, but it is our culture that defines why we do it.

Kinbaku: Affect and Effect

I had a moment of clarity after an afternoon spent with Naka Akira at his kinbiken meeting in Tokyo. For six hours, Naka sensei spoke and tied three different women. He didn’t teach or even talk about a single technique. There was no instruction and no hands on tying by any of the 30 people in attendance. What he did talk about was history, culture, and the heart of kinbaku. I couldn’t help but wonder what other westerns would have thought of the day.

It is the difference between appreciation and learning. No skills were shared. There was nothing to be “learned” in the strictest sense of the word. It was, however, a masterclass in kinbaku appreciation. It was the essence of why we tie as affect, rather than effect. (I will be writing a more extensive discussion of the day in another article).

I could not have been more grateful for the day. It was the kind of learning that, for me, helps me better understand myself, my partners, and my desires. It is also the kind of learning I feel like we are missing in the west. I think that we, as a culture of rope and kinbaku, are lesser for it.

Whether a space for that kind of learning and understanding will ever emerge in the west is, I believe, an open question. Whether it will last in Japan beyond this current generation is also a great unknown.