1. How did you get started in kinbaku?

My first exposure to bondage was at the age of five. I was a hyperactive and impulsive child who was also very mischievous. My mother started tying me to the bed every night to prevent me from wandering the house; she would also tie me to a chair as a form of punishment for misbehaving in school. I believe this was the root experience for my fundamental relationship to rope bondage. The physiological and psychological experiences I had in those early years would certainly inform my inquiry into this beautifully complicated and layered exploration of suffering and catharsis.

My specific path of discovery of all things kink really started at the age of thirteen, when I found a book called My Secret Garden in the trash bin of my apartment building in NYC. This book was written by Nancy Friday, who had compiled sexual fantasies from several anonymous volunteers and organized them into different sections based on specific fantasies. This was my first chance to learn about BDSM, as well as bondage particularly, as a sexual act and how rope affects people who wish to be tied. The book clearly piqued my interest and definitely altered my life.

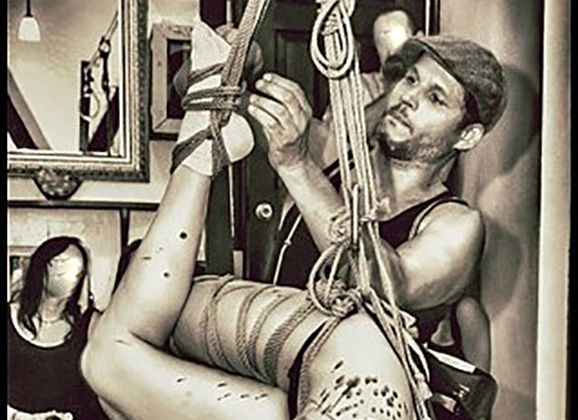

In 2006 I visited a friend who was living in Japan, and he took me one evening to see a Kinbaku suspension performance at a local BDSM club in Tokyo. I can’t recall who the performer was, but I do remember how mesmerized I was by the way he embraced, embellished and tormented his model with his rope. It was as if I had discovered a beautiful and deep refinement of my early and impactful experiences, and a way I could explore Kinbaku as an art form and a life path, in a healthy, consensual and deeply psychological way. I left that day knowing that Kinbaku would be something that I would learn. I returned home to the U.S. inspired by what I had seen, and set out to learn as much as possible using Japanese videos, magazines and what I could find online. Learning Kinbaku seems to come very naturally to me in regards to understanding anatomy, technique, tension, flow, efficiency and connection. I also attribute this to my decades of training in bodywork, Chinese medicine, martial arts and dance.

2. Who is your inspiration in the world of Kinbaku?

My biggest inspiration to this day is my partner and rope muse, True Blue. She was the first to acknowledge my passion and ability with rope and encourage me to take up Kinbaku as more than a hobby. Early on in my studies, I saw several performance videos with Esinem and Riccardo Wildties, to name just two, and these would inspire me to become a professional rope artist and performer, which led to the creation of Bondage Erotique.

In regards to my present inspiration, within the last year and a half, I’ve become very interested in the classical Kinbaku of the late Showa period (1926–1989), namely through the work of the Nureki Chimou and the revival of this style by his deshi Akira Naka, whom I greatly admire and respect for keeping this approach alive and well.

3. You have a lot of experience traveling and spending time abroad. How has that influenced your interest in kinbaku?

I was born and raised in the South Bronx, but my family is from the Dominican Republic, and I feel this ‘dual citizenship’ has always fed my adaptability within diverse cultural contexts and languages.

I started traveling abroad as a teenager, and spent years in other countries immersing myself in studies in music, traditional medicine and food, most predominantly in India, China, Brazil and parts of Europe. I have an anthropology degree, and know that cultural insight and interest in the human experience and psychology are deeply ingrained in the way I process information, learn and express myself. In my recent years this has translated to my studies of Kinbaku.

I believe that Blue and I entered the American rope scene at a very exciting and catalyzing time, in terms of Kinbaku and international influence. The rope revolution that has been going on in Europe over the last few years seems to have reached the U.S. and Canada with a wonderful influx of instructors, such as Hajime Kinoko, Kazami Ranki, Otonawa, Wykd Dave, Peter Slemrian, Gorgone and Hishi & Barkas, who have helped to raise the bar in regards to the level and quality of skill here in the U.S.

I am obviously a firm believer in learning through exposure to and immersion in different cultures, and so I find this change of tide to be necessary and invigorating to our practice of Kinbaku here in the U.S.

4. How different is what you do on stage from what you do in your private scenes?

Performances are exciting, and I enjoy sharing this beautiful art with a wider audience. My personal rope practice is a time for exploration, study and play. There is something precious for me when I play with my partner when no one is watching. It’s during these times that I can explore the meaning of connection more deeply, using rope as a conduit that helps to remind me why I continue to study this art. For me, Kinbaku is my practice, my meditation, my spirituality and my life. I heard Akira Naka say that he likes to think of his performances as the audience peeking through a keyhole at something very intimate, and so I suppose the core experience is the rope practice we do personally, and the joy of performance is the attempt to translate that private moment to an audience.

5. When you perform what kind of preparation goes into your performance? Do you rehearse specific ties, suspensions, and transitions? Or do you let things develop organically?

It depends on the circumstances. Both Blue and I have been performers in the past and feel that rehearsing is a good thing. We will rehearse if we have a performance that we want to creatively flush out, or a specific story arc we want to share. But on the flip side, there are times when we show up to an event and do whatever feels good in the moment. It’s important to develop the skill of spontaneity and improvisation so that you stay creative and inspired. Spontaneity is also vital in rope so that we remain alert and able to promptly respond in terms of safety and what I like to call ‘crisis management,’ which can always arise in a rope scene. For example, I tied five models for MBE whom I had never rehearsed with. Due to the circumstances, I was left to improvising based on each model’s body type, injuries and specific limits and capabilities. In order to be safe, I needed the ability to be spontaneous with each one. It also created an exciting, inspiring interaction with each model.

6. How did you get involved with Cirque Shibari? What is it and what can we expect to see?

My introduction to Cirque Shibari was through my dear friend Gorgone. She is excited by the concept of Cirque Shibari, and is working very hard to create a beautiful show that upholds the tradition, while it also innovates the art form and brings it to a very wide audience, most of which has never witnessed rope bondage. She asked us if we would be interested in being part of the show. We felt honored to be asked to participate in something so groundbreaking and also that it would be fun to be part of such a talented, dynamic group of performers and producers. At this point Blue and I have decided to be part of the show more as backup performers due to our teaching schedule and other commitments. We both do feel it will certainly be an amazing opportunity to open the doors for those in the mainstream who may be interested in this world of Kinbaku. You can expect Cirque Shibari to be headed to major cities around the world sometime in late spring/early summer 2015.

7. There have been a lot of Japanese bakushi visiting the states recently. What do you think the impact will be on this influx of new knowledge and perspectives?

I think the impact has been great, as I said earlier; we needed a good shot in the arm in America in regards to the quality of rope that was being done here. It’s good to see the bar being raised higher, and only good can come from this with regard to the quality and skill level of rope practitioners here in the U.S.

8. What is it that you love the most about kinbaku? What inspires you?

It’s becoming apparent that there are many ways to practice Kinbaku. It can be used to tease and torment, tickle and torture. Kinbaku is still evolving and is developing its own flavor outside of Japan that will meet the needs of our culture here in the West. We stand to learn so much from Japanese traditions and aesthetics, but we also should not dismiss our own perspective. For me, with my background in medicine and anthropology, I have been exploring and moving towards sharing Kinbaku not only as an art and a form of sexual play, but as a healing modality that can help individuals and couples develop skills and reintroduce the idea of connection, communication and intimacy in a culture where we’ve become more and more disconnected based on a stressful lifestyle and an overuse of technology. Blue and I are constantly intrigued by observing in our classes how people clearly are drawn to rope because they are looking so desperately to connect, even if they cannot name it as such. We see people in their 20s through their 60s, straight, gay, pansexual, monogamous, polyamorous, kinksters and hardcore sadists alike, who are incredibly ethnically diverse as well, drawn to rope. This inspires us greatly.

For those in the vanilla world who don’t have much knowledge of Japanese culture and rope bondage specifically, learning how rope torture can be a positive experience to play with can be very eye opening. Part of our goal in teaching both new students and experienced riggers is the idea that Kinbaku can be a way to facilitate space for their partner to explore suffering as a safe and cathartic process that can lead them to a state of emotional and physical transformation, and hopefully ecstasy. This outlook will allow those in our culture here in the West to digest and embrace the idea of torture and sadistic play that has been part of the Japanese psyche for many centuries, in a way that is accessible and doesn’t scare them off! This is a very lofty idea, but we personally wanted to step out of the box and do away with the clichés about bondage. This is the power of Kinbaku, for us.

For me, this beautiful art of suffering is making a full circle and evolving to become a form of sexual and emotional healing for those who are seeking that path.

9. How has your own style of kinbaku evolved? What are you doing differently now than you were doing even last year or a few years ago?

My style has been evolving in the last year to focus on the concept of Semenawa (rope punishment/torture) and the deeper meaning for me personally in regards to how I can use rope to elicit a polarity of sensations from my partner. Specifically, what this has meant for me is to really slow down and patiently wait, allowing each rope I put on to have its full effect. I also have been playing more with floorwork and partial suspensions, which I feel can be an overlooked area of practice as students and practitioners rush to transition from the floor up to full and dynamic suspension. I‘ve also spent the last year working less on a suspension ring, and more on the bamboo pole as a suspension point, which seems to work better with the classical Kinbaku style of the Showa period.

10. What is your favorite tie? What makes it special to you?

I really don’t have a favorite tie; I find each of the ties that I practice to be interesting and complete. What I try to focus on is learning when to use each tie appropriately and with the right intention. There are certain ties that I don’t use often and will come back to, so I can refresh my memory and see how my perception of the tie has changed, and further explore the deeper meaning and possibilities based on my present experience and feelings.

For a recent example, I can look at the futomomo and how my relationship with this tie has evolved with my rope practice. I initially loved the futomomo solely as a suspension tie, but lately have come back to it to explore a more rustic/organic Kinbaku approach. I think, over time, I have used six to eight different futomomos, each appropriate in its own way for where my rope practice was at during that time.