I first met Ugo san around 6 years ago via ViceMinister, an American resident in Tokyo, and, as a confirmed historian of rope bondage in Japan, he has since become my ‘go–to’ reference when interacting with new contacts in the Japanese scene.

Sin: Ugo san, how did you come to be interested in rope bondage?

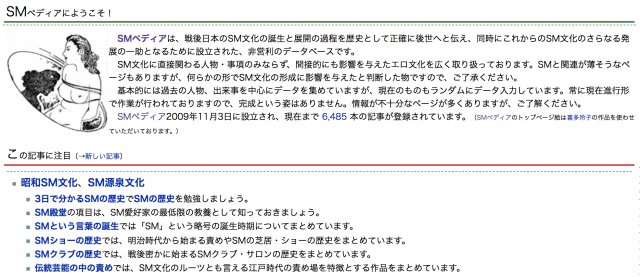

Ugo: My earliest memories of finding SM-associated emotions in my heart go way back to when I was 8 years of age. This was during the mid 1960s. At that time, among pupils in elementary school, Manga comics were the main source of our amusement. There were lots of good serial Manga works published in many weekly magazines. Of course, they were completely aimed at children, and then, did not contain any erotic materials or themes. However, children generally have greater sensitivity than adults, and they could find some erotic elements among these vanilla stories for themselves. I remember the strong emotions evoked when I read stories of kidnap, discipline, reorganization and restraint of the body, etc., especially works from Tezuka Osamau and Umezu Kazuo (see Fig. 1).

Sin: So when did the explicit sexual element appear to you?

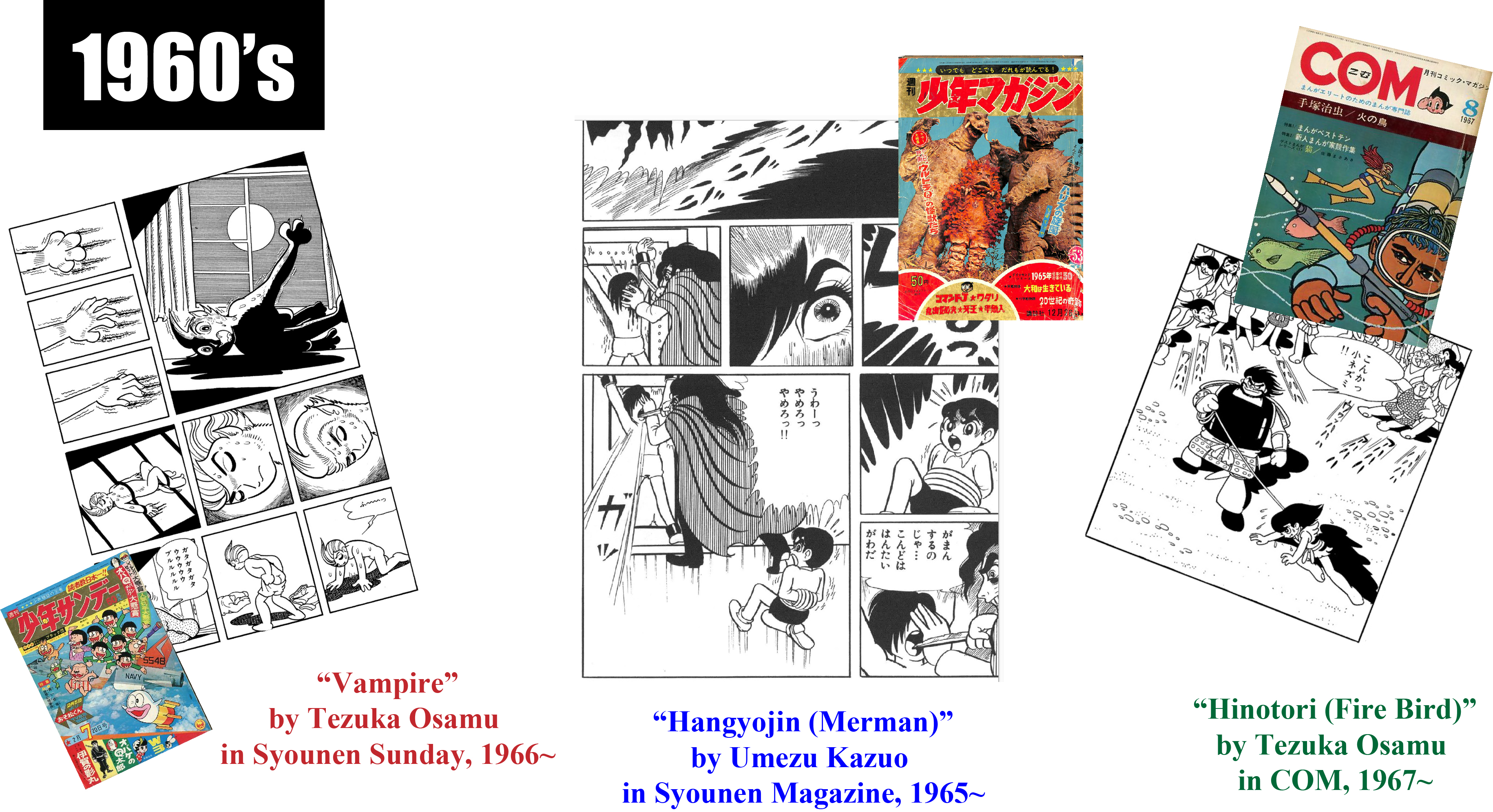

Ugo: The 1970s were the era of counterculture. The movement started worldwide in the mid-60s, and it penetrated into ordinary Japanese life. Creators were trying to dismantle established values and mass media were introducing these activities. Around 1970, I secretly started to watch TV programs broadcast after midnight after my parents went to bed that were intended only for adults.

Nowadays, we don’t see these erotic TV programs in major broadcasting anymore, but before the end of the last century, there were several that had erotic content. The 11PM was the reprehensible one, and they often introduced erotic activities in which SM related news (SM Film, SM Bars, SM Theatre, etc.) were included. Around 1970 sadomasochism begun to get more popular with the general public. Many SM magazines including SM Select, SM Fan, SM King, etc. were launched in the early 70s. Dan Oniroku, Tsujimura Takashi, Shima Shikou all appeared in The 11PM, although, at the time I didn’t register their names.

Additionally, there were many supposedly vanilla TV programs that contained erotic scenes. I liked to watch Play Girls, a drama about female detectives that contained erotic scenes in almost all of the stories. Sometimes, those erotic scenes were SM-based, and the heart of a senior-high school student like myself was vigorously enthused by these scenes. Even very normal costume TV or film dramas enjoyed by young children to elderly people very often contained Shibari scenes, as do many traditional Kabuki and Bunraku puppet plays. It’s in our cultural Japanese backgrounds that we enjoy Shibari.

During this time, it was common to find SM magazines for sale in very ordinary bookstores. Initially, I wasn’t brave enough to buy these magazines in the early 70s, but in the mid–70s. I summoned up enough courage, and started to buy them at a bookstore located in a neighbouring town. But still, I had strong feelings of guilt and shame to purchase them, and, after reading, I often threw them in the trash in a nearby park.

By the late 1970s, a new type of magazine was launched, in which there were not only very erotic materials, but also vanilla articles included, and this kind of decriminalized me to get them. New Self was the one such magazine, launched in 1975 from Green Planning with Suei Akira as an editor. Green Planning was the publisher that had published Bini Hon (‘plastic magazine’ – the magazine was sold covered with a plastic bag so customers could not see the contents before buying). With erotic photos from Bini Hon, Suei Akira focused on various alternative cultural activities. Suei Akira is regarded as the person who brought Araki Nobuyoshi to fame, and I enjoyed Araki’s work in New Self. At the time, Sugiura Norio also did photo shoots for Bini Hon, and his photos were used in New Self. I also knew the activities of Tamai Keiyuu from the magazine, who greatly influenced the emergence of the SM show boom in the late 70s (see Fig. 2).

When I went to university in 1977 and lived alone in Kyoto, my feelings of guilt to buy erotic magazines disappeared, and I started collecting SM magazines: Bini Hon, etc. There were so many SM magazines and their contents were very similar, so I don’t have any specific memories of them. However, I do remember that I was shocked by a story of Hara Kiri fetish in Sun and Moon, a magazine from which I began to learn the depth of the Hentai world.

It was 1981 when I first tied my girlfriend, as she was also interested in SM play. I purchased Asanawa rope in a knickknack shop, and it wasn’t treated at all (we didn’t even know about the necessities of pretreatment back then). We were not only interested in Kinbaku, but also enjoyed various types of play, including whipping, exposing, waxing, etc.

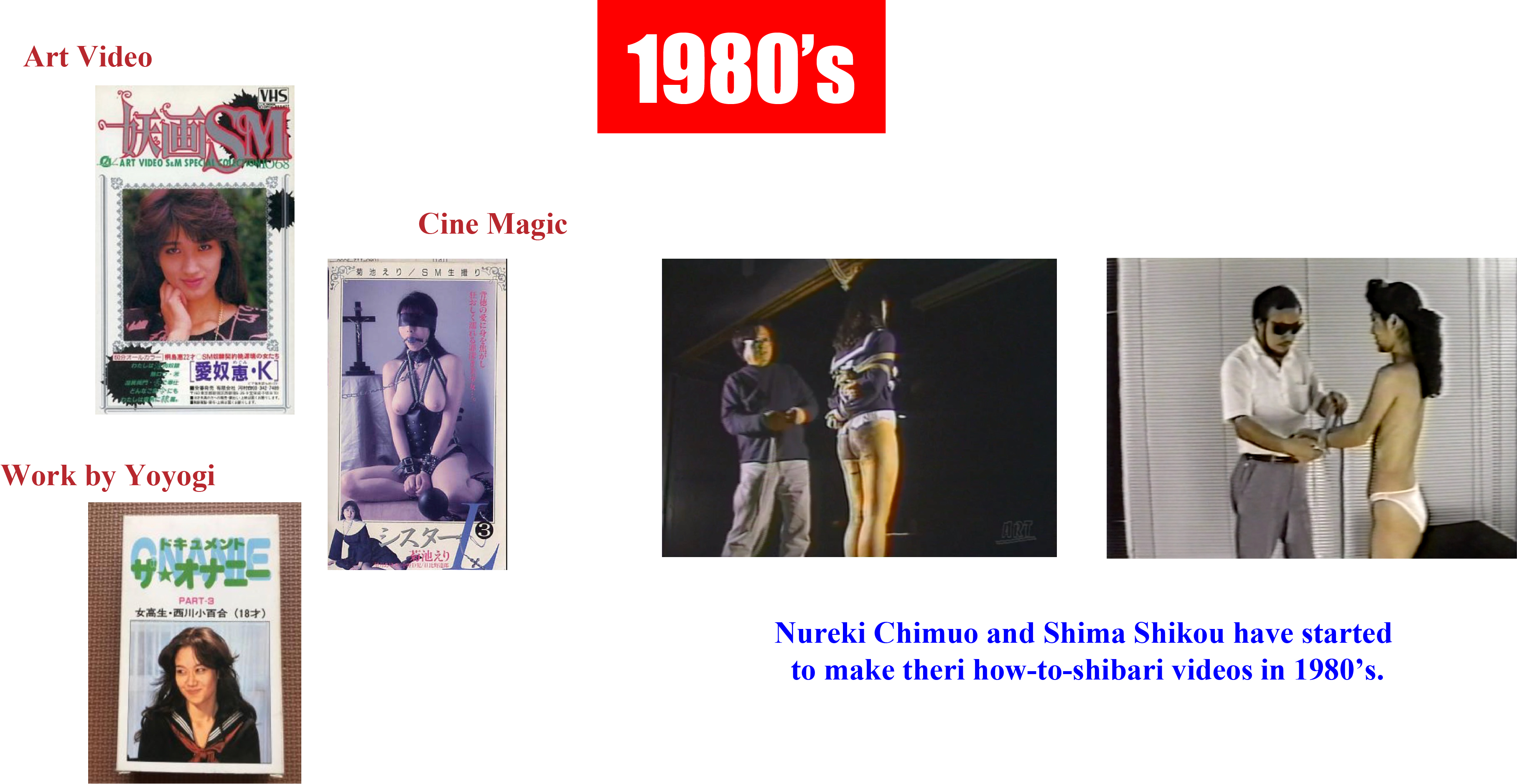

The 1980s was the era of SM video. Art Videos and Cine Magic both started in the early 80s. The price of these videos was still quite high for young people, but by the middle of the 80s, we could watch these erotic videos in a small booth. I frequently used these video booths and enjoyed the works of Art Video and Cine Magic. I now know that in some of these works Nureki Chimuo served as Kinbakushi. Along with these SM videos, I was deeply impressed with the work of Yoyogi Tadashi, who was one of the pioneers of Japanese AV (see Fig. 3).

After spending 9 years in Kyoto, I moved to Tokyo in the mid–80’s. Essentially, I was enjoying SM as a fantasy in my mind, watching videos or reading SM magazines. The girlfriend whom I tied for the first time was my only play partner up until this point. But, after 2000, I could easily find women via the Internet who were interested in playing SM games, and I increased my experiences of real Kinbaku play.

To improve my Kinbaku, I first learned technique from Nureki’s How-to videos. For myself at the time, Nureki and Shima were the only experts of Shibari that I knew about. They both made many How-to-Kinbaku videos. I loved both of them, even though their techniques were totally different (Shima’s Shibari is quite unique). It was difficult for me to master both techniques, and I happened to choose Nureki’s video for learning, and tried to mimic his Kinbaku by watching.

Then I discovered that there were several Kinbaku teachers in Tokyo. I chose Haruka Misaki’s classes and took my first lesson with her in 2007. She learnt her Shibari from Kai, a talented studio Kinbakushi and AV producer. Because her interest moved on from Kinbaku to anal play, I decided to find a new Shibari teacher, and took lessons from Osada Steve in 2009. In 2014, I started to take lessons from Yukimura Haruki, and this experience expanded and enriched my life with rope bondage. The details of what I learnt from Yukimura are available in the Yukimuran Studies discussion group on Fetlife: https://fetlife.com/groups/115140

Sin: Do you believe any western influences, e.g. John Willie’s work (1940s/50s Bizarre magazine), and his influence on Irvine Klaw – Betty Page, etc. may have had an effect on the Japanese SM erotic publication market?

Ugo: Yes, I think so. There were lots of publications that dealt with his or related works in Japan, which indicated that the editors or publishers knew that many readers also love his or the related works. Mutual influence between Willie and people in Kitan Club was also examined by Master K in his The Beauty of Kinbaku (2008), and I personally have a lot of respect for John Willie.

Sin: Do you believe that the different attitudes to the erotic and SM in Japan may have influenced how Japan became the first country to really open up about rope bondage practises, and that the invention of video led to some (e.g. Nureki) finding it easier to produce moving images?

Ugo: The first question is a difficult one to answer. First of all, for me, the erotic and SM overlaps. Even in a quasi–vanilla erotic scene, I will try to sense the flavour of sadomasochism. I don’t believe that different attitudes in Japan were behind this opening up about rope bondage. I believed that to enjoy, people had to separate the Kinbaku from the erotic.

For the latter question, definitely yes. New technologies have always stimulated creative people. The invention of video attracted many people who worked with photography or film around 1980, and so video helped expand their power of expression. Fujiki TDC analysed the history of the technologies of video and AV works very well in his Revolutionary History of AV (アダルトビデオ革命史 – 2009), although it is currently only available in Japanese.

Sin: I sense that the two words Kinbaku and Shibari have now come to mean the same thing to practitioners in our rope bondage world. Would you say there are any subtle differences, and if so, what would you say these are? For example, when Japanese business colleagues ask me what I’ll be doing at the weekend, there is always a very different reaction if I answer Kinbaku than if I say Shibari. If I say I’m going to be doing Shibari, the reaction is almost neutral, as if it’s interesting, but nothing more. But, if I use the word Kinbaku, there are lots of Ooo’s and Eee’s in astonishment, and I get the feeling that it is wiser not to mention it to the ladies I work with, or to management.

Ugo: Yes, I would agree with that Kinbaku and Shibari have subtle differences in their meaning. However, the difference is dependent on the user’s age, on their knowledge of history, local culture, their own personal history, and even the context of conversation. If you ask ten people, you will get ten different answers.

For me, Shibari is the word that I can imply various meanings depending on the context, whereas Kinbaku doesn’t have the flexibility for that. But, this may not be generalized, and other people will have different feelings.

We should note that Ito Seiu used both words. For him, Shibari meant what I think Shibari or Kinbaku means nowadays. Whereas Kinbaku was the word that represented a kind of historical motive of Kabuki play for him. For Ito, Seme (torture) was the equivalent term for sadomasochism, and Shibari was the main tool of Seme. But, this was around 1900.

Sin: So we could say that the distinction between the two words Kinbaku and Shibari have become somewhat blurred?

Ugo: I only know the example of Ito Seiu for the era around 1900. To conclude that, we should thoroughly research how people in that era used these words. What I wanted to say was that the meaning of a word is always drifting and changing. By the year 2050, people may use Kinbaku and Shibari with totally different meanings from what we have now.

Sin: I do not know how well you follow the incredible take–up of interest in rope bondage outside of Japan, and of the number of Gaijin foreigners specifically enthused by the Japanese scene. But, what I notice is how certain Japanese have altered their approaches to embrace more of the aesthetic elements, e.g. Kinoko Hajime, moving away from the sadomasochistic and the erotic towards art. I think we can agree that rope as a medium is so versatile, that it permits uses from very light quasi–erotic, to extreme hardcore play, and in this respect it allows people to play at whatever level they enjoy. How do you believe Japanese Kinbakushi view this western interest, and is there any concern that core cultural aspects may be being misrepresented?

Ugo: I always enjoy the evolution of culture. I love to see Yoga Shibari, Mindfullness Kinbaku, or something like that. I think the direction into which Hajime Kinoko is moving is the current one that society wants. He is doing the right thing. After importing Shōwa-style Kinbaku into the western (from the pre–1989 Shōwa period), people have the right to modify it so that it fits their philosophy, culture, society or era. Sushi has been spreading worldwide, and it has freely evolved into various styles, some of which, our Japanese didn’t expect at all (for instance, Sushi–Tacos in Mexico). This is fine and is the natural evolution of culture. You can concentrate on Naka-style, Kanna-style or Ranki-style Kinbaku, and also you can establish your own style by modifying them, if you like to do so. You mentioned core cultural aspects in your question, but I don’t know if any core cultural aspects exist or not. Our Japanese Kinbaku culture has a history of not more than 100 years, and it is still moving and evolving. It could happen that we have to go back to learn Naka-style, Kanna-style or Ranki-style Kinbaku in 2040 from western Kinbakushi. Personally speaking, I will stick to the old-Shōwa-style Kinbaku for the rest of my life, even though it may eventually become extinct in the near future. I am not personally interested in doing quasi–erotic Kinbaku. But, do I like to see it.

Sin: You were a great help to me when I was editing my first book Year of The Bakushi about my experiences in Japan, especially concerning terminology. What I’ve picked up on since is how much of this terminology is recent and invented for descriptions, e.g. Matsui Kenji naming ties after Kansai clan heraldry because of the visual similarities, or Nureki, because he needed a term to name the tie he was showing or teaching in a video. It has also been suggested that while not the first to tie in such a way, it was Aotsuki Nagare that really perfected the Futomomotsuri. How much of what we think are historical ties have a more recent history than we believe?

Ugo: Most of the terminology of Kinbaku has been invented very recently by someone ad hoc, and shouldn’t be taken too seriously. Some people might say that Japan has a long culture of Hojōjutsu, which has its own terminology, and this is true. But the influence of Hojōjutsu to Kinbaku is very limited. Most of our Kinbaku terms were invented after the Second World War, and we can freely create new terms if we wish. I should add the fact that both Akechi and Yukimura weren’t very interested in the terminology of Kinbaku, and every time they were asked about the names, they might reply differently. Because Nureki was an editor and a writer, he may have been more interested in names for Shibari ties. It’s now that the people who run Kinbaku Dojōs recognize the importance of terminology and organizing their terms.

Sin: If we separate the publication and film/video depictions of rope bondage in Japan from the live show situation, I’d like to explore not only the individuals, but also how this developed. From my limited knowledge, I see several evolutions in Japan occurred during the 1960s: Karaoke, love hotels, etc., and of course, rope bondage as a sadomasochistic and erotic live performance. On a cultural level, what do you believe changed to permit live SM performances during this time period, what was the chronology, who were the major players, and where were the locations?

Ugo: If I focus on the 1960s, we have to think about two separate activities: Strip Theatre (including movie theatre), and Underground Theatre. Of course, it is difficult to completely separate the two, because they were partly overlapped and mutually associated.

Strip theatres (strip joints) were at that time popular all over the world. I don’t know the exact numbers, but very many strip theatres existed during the 1960s all over Japan. Most of them were simple nude dancing, but sometimes they presented SM style shows, some of which were depicted in Kitan Club magazine. In the mid–60s, film theatre, especially for erotic films that made a type of short stage play performed by adult actresses and actors was very popular and made lots of money (I was too young to see these). Dan Oniroku and Nureki Chimuo were writing scenarios for erotic movie theatre plays, and of course, in their scenarios, the play included Shibari scenes.

And, as I stated above, the 1960s and 70s were the era of counterculture all over the world. Young creators tried to search for new ways to express their message. Underground Theatre was the new artistic direction, and there were many groups headed by famous leaders such as Terayama Shuji, Sato Shin etc. Mukai Kazuya was one such person, although he was not so famous, and he performed live SM-related plays, again, often covered in Kitan Club magazine. Osada Eikichi was influenced by Mukai to start his own SM show. However, these activities were known to only for those who were interested in SM.

Tamai Keiyuu was one organizer of Underground Theatre, and he was aggressively bringing “Eros” into his plays. He finally started his periodical SM theatre show in Tokyo in 1976, in which he invited Osada Eikichi as a supervisor of SM. As stated above, before this time, Osada was making his shows almost in secret. However, Tamai was different. He opened up SM shows to the public. Tamai’s activities were followed not only in erotic magazines, but also in the vanilla media, and this brought an interest in more to come and see a SM show in his theatre. I think of Tamai as the person who established the modern SM show. However, Tamai himself was not a person who loved SM, but was just a theatre president who understood the power of SM as a theme for plays. Thanks to him, Osada Eikichi became popular, and Sakurada Denjiro started his own SM show after he worked as a member of staff in a Tamai theater. Later, Sakurada eventually brought in Akechi during the 1980s.

Tamai, Osada and Sakura all started to make their SM shows in Strip Theatres in the 70s, overlapping with the Underground Theatres.

Sin: And so with the sad demise of e.g. DX Kabukicho SM/pink theatre, do you think this kind of place to see SM and erotic rope bondage will return after the Tokyo 2020 Olympics cleanup, or do you think we’ve seen the last of this kind of venue, and the authorities will prevent a return?

Ugo: The Strip Theatre culture is dying away. They will not come back again. It is very sad. People should go to a Strip Theatre before they become extinct. Now, we have only 20 Strip Theatres in Japan, and soon one of them (DX Kabukicho) will disappear.

Sin: How much do you know of Akechi Denki, and how would you place him in influencing the Japanese rope bondage scene?

Ugo: Sadly, I didn’t have the chance to see him. Japanese Kinbaku culture started with Ito Seiu, and was nourished by Minomura Kou and others, then maturated by Nureki, Akechi and Yukimura. I place him in a very important position.

As I said, for me, Nureki and Shima used to be the only people from whom I learnt Kinbaku. I was getting to know many Kinbakushi, but, for me, they were just derivatives of Nureki. But, I was shocked when I watched Akechi’s Shibari in a DVD for the first time. It was different from Nureki’s. The distance between the person to tie (Nureki or Akechi) and their models was totally different. For me, the distance between Akechi and models was kind of nothing, and he seemed to invade into the model’s inner self, which thrilled me. He was really a person alone, and nobody can mimic him.

Sin: And who else would you say have contributed most to influencing others?

Ugo: I hesitate to mention about individuals who are currently active. For those that have passed, I have to highlight too many people.

Sin: I’m aware of many Kinbakushi seemingly unknown outside of Japan. Are there any currently active that you would recommend westerners get to know better?

Ugo: I think most of the currently active professional Kinbakushi have already been invited abroad, although I am not sure how professional should be defined. Some professional Kinbakushi may not yet be have been invited, but their movies are available via the Internet. Also, I would note that there are many very good female Kinbakushi in Japan, who should be known outside. As you said, there are so many good amateur Kinbakushi, but most of them don’t want to be open to the public.

Ugo san is the administrator of the online encyclopedia of Japanese bondage and related kinky activities http://smpedia.com, incompletely reproduced in English at http://www.nawapedia.com