Last week, I made the mistake of logging onto Fetlife and reading some rope posts. I really should know better.

I came across a rope incident report and found myself thinking about why it is that so many injuries are happening and how they are handled.

There is of course, the requisite “mea culpa” followed by the posts about how very brave people are for publicly admitting their errors. We all learn the lesson that “injuries are inevitable” and that it even happens to very experienced riggers (some have been tying for years now) and how it is a warning to us all.

It has become a performance so standard that it is almost its own genre, rope apologia.

In this one case, our brave and somewhat defiant rigger was also full of bravado, a hero in the face of cruel fate that brings to us both injuries and bad feelings associated with them. But they will fearlessly soldier on, continuing to do their “intense suspensions” and teaching their rope classes.

The core of the problem for me is that almost never do these fearless confessions include the two most important lessons. The first is that injuries and mistakes are telling you that you may not know as much as you think you know. And the second is that the tie that you thought you had mastered (usually because you have done it so many times without incident) you didn’t understand as well as you thought you did.

I speak from experience on both of these issues. I can trace all of the injuries I have caused back to two sources, my own ignorance and my own incompetence. We all have those two problems. And we all can correct them with time, education, and practice. Well, perhaps not correct them, but at least be more aware of them and decrease the risks associated with them. We can also then do a much better job of making our partners aware of the risks they are taking when they tie with us.

The bigger issue for me is not how people tie. As long as everyone is on board, consenting, and willing to take the risks, people are absolutely free to do whatever they want with their rope. I am very much a member of the “rope is dangerous” school of thought (as are lots of things people do in BDSM).

Where I part company is when it comes to teaching.

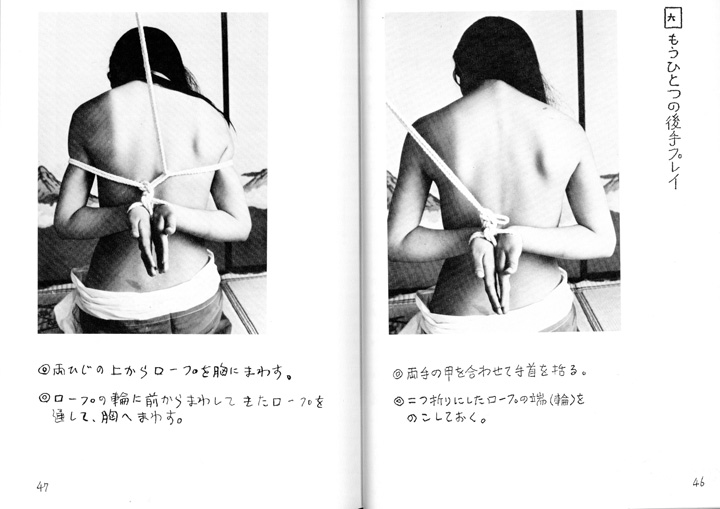

In the last case, I started to look at the pictures that the person who did “very intense suspensions” had posted. Two things jumped out at me immediately. The first was that these images were designed to replicate the look of ties done by some very well known Japanese bakushi. The second was that they were full of very weird choices.

By weird choices I don’t necessarily mean dangerous choices. It was much more a feeling that the person knew what they wanted the final tie to look like, but didn’t really know how to get there. Little things, like where rope was attached to bamboo, where and when (and at what angle) different ropes crossed each other, as well as some other minor curiosities that didn’t ring any alarm bells, but just looked weird to me.

Partly those things just looked bad to me. But more important, they revealed, at least in my opinion, that the person tying them didn’t understand some very basic principles of how those ties are constructed. That concerns me not because it was dangerous per se, but more because it makes me think that the person tying doesn’t know if it is dangerous or not.

If you know technique A is safe and why it is safe, you are going to have a better chance at constructing a safe tie than if you use technique B, not having any idea whether it is safe or not. Worse yet, I don’t know if this person even knows the difference between technique A & B. They actually may think they are doing technique A when they are doing B, and so on.

We are talking about the fundamentals of construction. One doesn’t need to understand the physics, engineering, and force vectors behind it. But you do need to know “pulling here is going to make things tighter there” and “connecting these two things is going to make this tie unbalanced” and so on.

When you learn these ties, even studying in Japan with the top people, none of this stuff is likely to be explained. It is more or less baked into the ties. It is the kind of thing you start to understand after years, even decades, of study of a particular ryuu. But when it comes to teaching, it is also the most vital and important stuff to pass on.

Those lessons, at least in my experience, when studying in Japan come in the form of “No, not there. Here.” That’s it. You are shown and told. If you press for a reason why, you are likely to get a relatively short answer that will require a lot of unpacking.

The major problem with this is that when you learn rope, particularly the way most Westerners learn rope in intensives or workshops, you are learning to be competent, not knowledgeable. That is distinction is incredibly important when it comes to teaching. Competence is important for keeping your partner safe. Knowledge is important, even essential, for teaching others how to become competent.

Competent bakushi don’t necessarily make good teachers.

I saw a recent video complaining that not teaching was a form of “gatekeeping” and that if you have the knowledge and don’t share it, you forfeit the right to complain about other people doing dangerous things. There may be some truth to that if someone is intentionally withholding knowledge that could help keep people safe.

But often, I see exactly the opposite, an almost desperate desire to show others what has been learned or seen. People who learn to tie and make Instagram-worthy pictures or end up on “Kinky and Popular” on a regular basis are often seen as knowledgeable, when they may actually be displaying a high level of competence.

When talking to people about the latest incident, I was surprised by some of the questions I got from some people who were asking what I found wrong with the pictures the person was posting. These were experienced people who have been studying a long time, tying with a very high level of competence.

Competence is important. It is what is going to keep your partner safe, but it doesn’t mean you understand what you are doing and why you are doing it, which are the minimal qualifications for teaching someone else how to do it.

So how do you know when you are knowledgeable and not competent? At some level it is a personal decision. But some indications for me are that if you can’t have a substantial conversation about the tie you want to teach without the rope or doing the tie, you probably don’t have much knowledge about it. If you can’t discuss the various choices you are making at different moments and how each of those choices shape and define the aesthetics, feelings, and sensations of the tie, they you probably don’t have much knowledge about it. If you can’t define what are the more and less important moments in the tie and how you can vary the tie based on what effect you want to create and how that enhances or mitigates the risks of the tie, you probably don’t have much knowledge about it.

That said, just because you aren’t knowledgeable in those ways does not mean you are not incredibly a competent, safe, and amazingly talented bakushi. There are plenty of people out there who may not have the kind of knowledge I am talking about who I would recommend to anyone wanting to be tied and whose photos and performances I enjoy tremendously.

The other option, which is a much tougher route, is you can wait to be told.

In most cases if you ask a Japanese person, “Would it be OK for me to teach this?” they are going to say yes. If you ask, you will get the answer you want, mainly because most Japanese people really dislike saying “no.” It doesn’t mean very much. What it actually means is you have put them in a very uncomfortable position and they are responding with the answer that will make that awkward situation go away.

It is an entirely different situation when your teacher tells you that you should teach. It is the signal that they see you as not just competent but knowledgeable as well. It is not just permission, it is something more. It is more like a directive.

If teaching is your idea, it doesn’t mean very much. If teaching is their idea, it means a lot.

If rope education is to move forward in the west, I think we need to do two things. The first is to start recognizing the distinction between competence and knowledge when it comes to sharing how to do ties and to have our educators spend more time on the latter. The knowledge part is hard work. It is often times boring. It won’t get you any likes anywhere. It will only make your pictures look better in the eyes of very few people who will notice the small differences between your ties and others’. There really aren’t any rewards for it.

The second is for people to stop teaching things they aren’t actually knowledgeable about. That is going to be the heavy lift, because most people simply don’t know what they don’t know. And very, very few of them want to find out. Worse even is that when you starting becoming knowledgeable, you realize the really cool, crazy stuff you are going to get ego gratification for teaching is a lot more complicated than you realized. You start thinking “I can’t possibly cover everything I need to cover for a basic wrist tie in a two hour class!”

Teaching rope has a lot of rewards for people: Social capital, access to play partners, ego strokes, social media celebrity. Stepping away from that kind of feel-good feedback and recognition is hard.

If you want to become knowledgeable about rope, I suggest that the way forward is not learning more ties, patterns, suspensions, or technical skills. The way forward is conversations. Talk to everyone you can find who knows more than you. Seek them out. Not to learn some technique, but to learn why they tie and why they make the choices they make when they tie.

Talk to rope bottoms. Learn from them. They know so much, yet rarely get asked. All of my best teachers have been rope bottoms.

All of these things are going to take work, time, and effort. But I also believe that it is going to make rope a better, safer, and more fun experience for everyone involved.

Spanish Translation Available Here