No matter where you live today, the rapidly growing information sharing streams have helped our communities discover, grow and evolve.

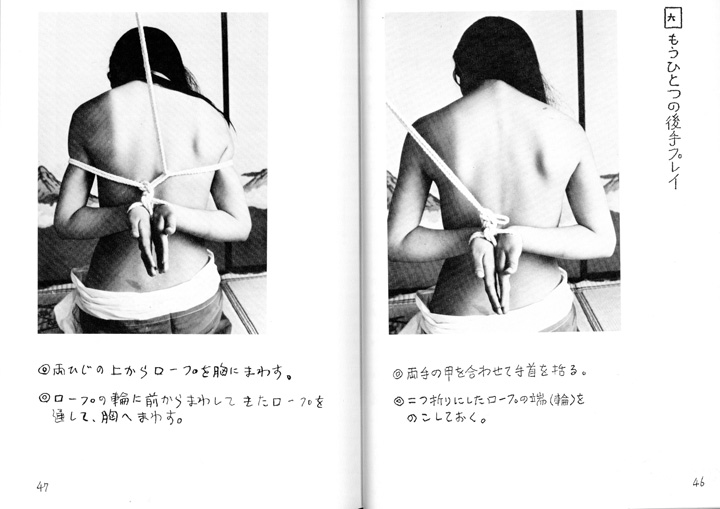

Whereas just two decades ago shibari or kinbaku, whatever you want to call the Japanese art of bondage, was known and taught to just a few outside a small community in Japan, today it has become internationally known in many countries around the world.

Schools teaching kinbaku have sprung up in Europe and the US and global events are being held despite Covid taking us a step back for a while.

This has not been a one-way street. As more westerners with different backgrounds, such as martial arts, circus experience and aerial arts knowledge, adopted classic shibari techniques, they have introduced ideas of their own.

They have influenced the work of some of the Japanese masters and have helped make today’s kinbaku a living, flourishing practice world wide.

Despite this massive flow of knowledge back and forth, and some traditional ties and practices being universally adopted, some cultural differences in the practice of shibari are quite evident.

It is my humble opinion that this is a result of shibari, at the end of the day, reflecting to a great extent, the personality of the people practicing it. Beyond certain technical knowledge you must master, what you bring to the scene is yourself – the customs of your local BDSM community, your set of beliefs in general, your view of what a rope interaction should be like, what its goals are and more.

As a result I have observed during my personal experience of about 10 years of tying and teaching rope in several countries, some distinct cultural differences between how different countries adopted Kinbaku.

Obviously, this is a bit of a generalization but I believe many of those who witnessed different kinbaku cultures would tend to agree with me. In Italy, for instance where today Naka Ryuu is prevailing over other schools, the emphasis would seem to be on aesthetics, technical proficiency and a tendency to follow along the lines of classical work first introduced by Naka Akira to Europe a few years ago. Suspensions tend to follow closely what is currently taught by Naka in his workshops and improvisation kept to a minimum.

In Germany, perhaps also due to the origins of the Osada Ryu master, Osada Steve, you find the two schools interact and influence each other with German efficiency and preciseness a strong factor in the way people tie.

An interesting discussion I had with a leading German rope top was about her being criticized by her peers for having “messy tsuri lines”. As one who favors functionality and speed over esthetics, her tsuri lines seemed more than fine to me.

Unlike the former, Russian shibari is much less focused on prefixed patterns and rules and the common word you would find people looking for in their rope play is “action,” meaning fast, challenging and more aggressive rope play, combined with much more impact and a sadistic streak, compared to what you would find in the rest of Europe.

The general view of the models is also a much more BDSM-oriented, submissive view and less the “model” and “lets see what you can make me feel” attitudes one would sometimes find in western rope bottoms.

In the US, things have also taken a flavor of their own. For better and for worse, it would seem that the US rope scene is geared much more towards the technical, and much less towards the human interaction that was at the heart of Shibari of such masters as the late Yukimura Sensei.

I’m probably going to be scolded for not being PC, but in many cases it would seem to be a very “paint by numbers” exercise with the goal of posting a social media picture at the end of it.

In a workshop I gave pre-corona in the US to advanced riggers and bottoms, I asked them to tie their “go-to” TK.

After that, I asked the riggers what it was that they wanted their bottoms to feel and asked the bottoms what they actually felt.

Some were even surprised by the questions, their answers leading to a wonderful three hour workshop on how to create feelings, emotions, and a shared experience with rope.

In my home country of Israel, we have embraced kinbaku in recent years and are growing fast.

Living up to our reputation as a fast moving startup nation we already have three venues that teach shibari in the Tel Aviv area. We have also had the benefit of learning from some of the leading rope masters of our time and have pretty much created a fusion of more than one school of rope.

One of the things that always stands out for me in our local scene is how, true once more to our reputation, we have no patience to learn the basics and master them before we move on.

To illustrate this trait, I will share an experience from a beginner’s workshop I gave. The participants were novice to rope and after a long six-hour workshop we called it a day.

Once finished, one of the participants told me that the workshop was a great disappointment to him due to the fact that we did not teach suspensions during the class.

My response to him that I was doing Western bondage for years and two years of shibari before I did my first suspension, fell on deaf ears.

Having said all this, do I think one culture is better than the other?

Definitely not.

Quoting the great late Yukimura in an interview I once read with him “Rope is free”. Your rope scene reflects what and who you and your partner are, and if it works for the both of you – that’s all that matters.

Enjoy your journey with rope and let’s keep exploring and advancing this wonderful practice of ours.