When Akira Naka tells the story of how he learned rope, he begins with the story of Kinbiken, Nureki Chimuo’s monthly rope salon in Tokyo that Naka san attended for five years. During that time, he watched, observed, and eventually assisted Nureki sensei with those events. It was close to two years before he was able to even touch rope and longer until he would actually tie himself.

In the West, such a story is often understood as a test of patience or a rite of passage. In Japan, it may be seen somewhat differently. The idea of building a context for rope is something we don’t understand very well in the West and we teach even less. In part, because we don’t have the same kind of patience and in part because we don’t have the same resources to fill that context and understand things in the same way.

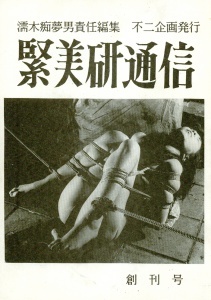

The value of Kinbiken was not simply in the transmission of technique nor in establishing a particular style of kinbaku. The value was in shaping a sense of what kinbaku could look like and, more important, feel like. Not only was Kinbiken a teaching environment, it was also a photo salon, the basis for videos, and the subject of multiple publications, books, and articles. Kinbiken itself was always more than just a monthly meeting, it was a context for kinbaku. The name itself is a shortening of the full description, Kinbakubi kenkyūkai, or “Beautiful Bondage Study Group.”

Understanding Kinbiken can provide some greater insight into the history of rope in Japan, as well as provide some points of reflection for thinking about how we might interpret kinbaku in a western culture.

Recently, a discussion was started in Fetlife about the concept of kotobazeme, literally “word torture,” in response to several of the interviews posted here. It occurred to me that it was a concept that was very difficult to understand from a non-contextual point of view. As I understand it, kotobazeme is essentially saying the right thing at the right time to help build the context of the scene. It will differ every time, based on the people involved and the energy and flow of the scene. It seems impossible to describe it as anything more than “using your words” to help create a scene or headspace.

Kotobazeme illustrates a feeling I have about Japanese rope. Kinbaku is never just about technique. Of course, technique matters for safety, for effect, for aesthetics, and so on. But the essence of kinbaku, for me, is not in any particular element of it, but in how those elements come together to create a shared moment. As a rope top, we are more than just riggers, we are curators of experience.

Knowing technique is like understanding the vocabulary of a language, but none of the grammar. You can use it to communicate in the most rudimentary ways, but to fully express yourself you need to know more than just words. You need to know how they come together and how they are related to other words, stories, and ideas.

A good rope scene has a grammar. Watching Nureki tie is something of a masterclass in grammar. I had the privilege of doing it in person in 2011, for a photo shoot he did for Mania Club magazine. His technique comes across as effortless. The effect on his model, however, was intense. I understood watching that is was more than just the rope that was creating the scene.

There are many reasons to approach rope this way, but there are also reasons why we need to think seriously about the way we teach and think about rope in the West.

Perhaps the biggest risk, however, is for safety. More and more, I hear Western rope tops running into problems when they take a tie they have learned from a workshop and use it without giving thought to its context. We teach rope as if the content and context were separable.

When I read accident reports online, they often begin with a statement “We were doing an X-style suspension.” Almost never do they start with “We were doing a rope scene.” What is the difference and why does it matter?

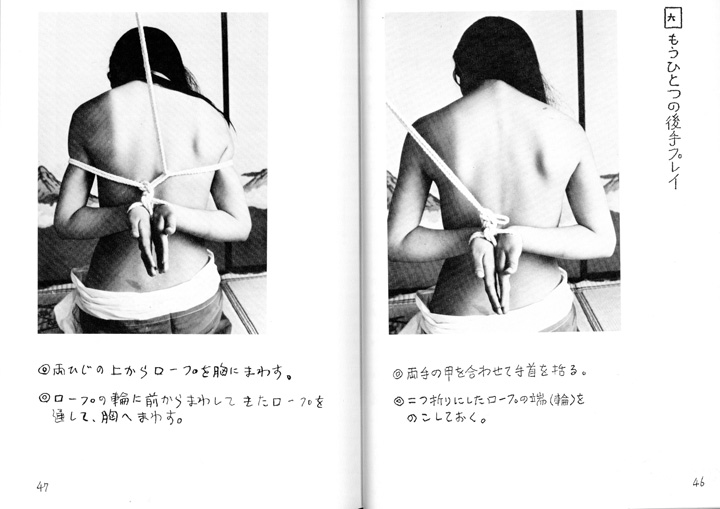

I am lucky to own a few dozen videos of Nureki’s Kinbiken workshops, many of the same ones that Naka likely attended as part of his learning rope. What is always interesting in Kinbiken sessions is how they start, how they build, and how they end. There is a gradual development. The scenes always start slowly, with basic ties, with long pauses for discussion and photography. Each segment is layered and built. The tie progresses, with each addition adding to the effect. The accumulation is not just of rope, but also emotion, psychology and physical response. There is beauty and elegance in such a progression, but there is also a measure of safety.

By the time the bottom is in a suspension, 20 or 30 minutes will have passed and a context will have been built. There is no sense of a “Nureki-style suspension.” There is only a Nureki-style scene that ends in a suspension (usually but not always). The bottom is both becoming acclimated to the intensity but also their body is creating an almost euphoric feeling (not unlike a runner’s high) which further protects them and allows them to go deeper into rope space.

It is easy to get bogged down in discussions of what something means or how to do a particular tie. The reality is that in an art as complicated and fluid as kinbaku, things mean different things at different times. Even more to the point, things mean differently at different times. Learning those differences and how to respond to them is not a matter of technique; it is a matter of experience, of feeling, and of empathy.

Understanding that nuance and the complexity of the context seems to me to be vital for understanding kinbaku at all. Spending time with Nureki’s Kinbiken, and works like it, might help us begin to understand kinbaku as something more than technique.