Lately I have been reviewing a lot of older style rope, primarily focused on Nureki Chimuo’s instructional videos from Fuji Planning. I am really happy that I am able to make those available to people for the first time in the West on my download site at Japanese Bound.

Apart from just making a sales pitch for these videos, I want to outline a couple of reasons why I think they are important for the Western rope community, not only as an historical documentation of where many of our techniques originated, but also as a point of discussion for where rope is going, particularly in the West.

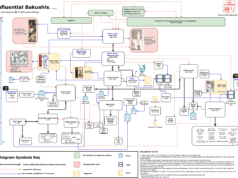

As most readers of Kinbaku Today, already know, Nureki Chimuo had a wide and pervasive influence of rope and rope culture in Japan. He was an author, editor, and prolific bakushi. His work with Sugiura Norio defined the aethetics of kinbaku in Japan for decades and his influence lives on perhaps most directly in the work of Naka Akira, who is widely acknowledged as Nureki’s sole deshi.

One of the most important things about Nureki’s work (and I would extend this to most of those who follow in the line of Minomura Kou) to me was his focus on using rope to create an effect and a response in his partner. His goal was always to develop a tie in concert with his partner’s responses to his rope. Finding the edges and limits of what his partner could endure, enjoy, and experience. That meant every part of every tie mattered.

To watch Nureki tie was always a masterclass in understanding progression, the creation and building of various forms and forces which would elicit a response and which would create a feeling of both endurance and ecstasy in his partner. Often those progressions would end in a suspension, if only as a way to maximize the tension, pressure, and intensity of the kinbaku. But suspension itself, it seems to me, never really seemed to be the point. It was only one more tool, never the end point or the goal of the tie itself.

We spend a lot of time dissecting and learning ties themselves, but very little time understanding the dynamics of scene building or rope progression.

When I see innovation in rope today, which as been happening at an incredible rate, it almost always seems geared to the question of how we make suspensions safer. The evolution and number of versions of the takate kote alone in the past five years have seemed to be focused almost exclusively on this problem and almost always targeted at the goal of making dynamic suspensions safer for the bottom.

I have no intention of suggesting this is not a praiseworthy goal or that we should stop doing that kind of work. Safety is important and performance based kinbaku has undoubtedly become the norm in the Western world of kinbaku (and arguably in Japan as well). What I do want to suggest is that we have been missing an series of opportunities to understand rope, not only historically, but as a future path of learning, development, and exploration as well.

There is an entire history of rope that has either been overlooked or discarded as uninteresting or useless because it doesn’t fit into the performance model of kinbaku. These ties, some of which are suited only for floor work, static suspensions, or partial suspensions, tend not to be taught, understood or developed because they, frankly, would be dangerous in the context of dynamic suspensions or show-style kinbaku.

When we remove these from our repertoire, we need to ask ourselves what we are losing and of what we are depriving ourselves. Showa era rope has a lot to offer if we broaden our perspective to think of things like shame-based ties, predicament bondage, tying to objects (bamboo, hashira, and furniture), ties for exposure and sex. The list goes on and on.

In the rush to learn suspensions, I believe we have left many other venues unexplored. Looking back at rope from the era of Showa, there are remarkable constructions and ties that accomplish many of things beyond putting someone in the air.

It is my hope that as we look back at the history and development of kinbaku, we can think about mining the past not only as a series of techniques, but also as a philosophy and understanding of what kinbaku can be. Doing so opens up new ways of thinking and provides us with the impetus to develop and innovate in ways that can help makes us more connected to the people we tie and who tie us.

View Nureki’s How to Tie Series Here