KINBAKU TODAY CHRISTMAS DEBATE

The COVID crisis has given us all pause for thought. Seeing how Kinbaku has evolved, is a new era appearing on the horizon, and what will impact its evolution?

I had the opportunity to facilitate a virtual discussion about this with Ugo san of SMpedia, Marc BeShibari and Sin. Their valuable insights and honest assessments led to a very lively discussion, and I humbly thank them for their participation.

Rope bondage from Japan has entered the mainstream in part due to western influences, and has been predominantly taught in a school style approach. Much has changed since the early days of the pink industry in Japan. But is it now at a turning point? What led to the current state of rope bondage, what is the potential future, and what would people like Nureki, Osada and Akechi think of it today?

Sin: 15 years ago, a Japanese and a westerner with confirmed martial arts backgrounds independently started a type of schooling of, predominantly the technical aspects of rope bondage. This approach became quite successful in the West, but doesn’t seem so fruitful with the Japanese. Maybe Ugo will correct me, but there appears little established teaching before this, and certainly not the westernized Dōjo/workshop methods. Individuals mostly got their inspiration from magazines, films, videos and live shows at pink theatres.

Ito Seiu was into his seventies before showing confidantes how to tie, and certainly not the technical alone. Nureki lectured in the mid–1970s. Osada and Akechi added displays to their SM–erotic acts with Seminar and Phantom shows respectively. Arisue Go and others encouraged people to tie. But terming any of these as formal schools is a massive leap. It would be more common to find groups of compatible souls where maybe one had greater experience, but there was plenty of mutual discovery beyond just the technical.

Until western influences began commercializing, certain Japanese terms were inconspicuous. Nureki is recorded as vehemently ridiculing notions such as Deshi, and from conversations with close contacts, it’s clear Akechi would not have approved. Absurdities such as ‘Shibari evolved from Hojōjutsu’ are disappointing, concreting ‘New Truth’ for marketing purposes; a prop to justify product. Hojōjutsu is interesting, sure, and sadomasochistic play, including Kinbaku in Japan was always influenced by punishment. But connection is as spurious as the medieval torture chamber is to the BDSM dungeon. Direct lineage is, at best, fanciful.

My view is very ‘broad–church’ – individuals are entitled to enjoy rope bondage as they wish: yoga, aesthetic, sadomasochistic, erotic, martial art, etc. So, I see how by discarding the underlying cultural–societal erotic, even grotesque sadomasochism common in Japan, the technical sanitized is undoubtedly easier to package for the West.

But there are crucial elements that aren’t easy to incorporate within this stripped–bare inflexible style of education. It would be better to understand how everyone’s journey is different, and guiding individuals to their own paths rather than copying somebody else. Even one–on–one, this requires the teacher to be able to impart, and the student to absorb and process wisdom. It cannot be done within a group, a fixed program, from books or visual media, or grounded within a day. It has to be a slow evolution, requiring empathy and maturity, and it also isn’t easy between diverse cultures struggling to be understood.

I have come to think that Japanese Bondage is an invention and the segregating term Western Bondage didn’t exist before it was first coined. Rope bondage is universal and we have our own words for Kinbaku or Shibari. The difference is the Japanese mindset and their influences. We have contrasting characteristics, and I see subtle components in their bondage beyond the rope. However, explaining how they function to the West has proven to be somewhat of a challenge.

Logographical and alphabetized languages are difficult to translate, and westerners picking out Japanese words for their own context can appear absurd. It’s a problem in the other direction too. Sadly, we don’t have lingually gifted, objective Japanese aficionados who can communicate well to a western ethos.

Most people, including Japanese Kinbakushi enjoy being treated like VIPs. I know some who are loathe to interact and yet surpass the skills most in the West encounter. Maybe they don’t wish to compromise their integrity. Commercialism is a demanding beast. One can turn professional with the best intentions, but when the money has to be in the bank, things change. A good example is a friend who for years followed an exclusive dedication to Akechi – the predominant influence of the majority of my generation in Japan, because he raised the benchmark so high. But now this devotee has the logo, the ‘Ryū’ and ‘Deshi’ to defy all logic beyond the commercial.

The last decade saw a monumental shift in societal attitudes to kink. We need to figure out the How’s and Why’s, and this needs ongoing deliberation. Naturally, growth generates demand requiring supply, and can promote narcissistic opportunists. They are, however, fairly easy to spot. They’ll feel entitled to be the sole source of authority, attempt to monopolize, and sabotage any perceived competition. Their revenue and reputation quash what’s best for the individual. They’ll promise false hopes, like learning complex elements that cannot be easily coached. They’ll prey on novices, exchanging minimum value for a grandiose sense of entitlement, cultivating a wave of unwitting followers to justify them, doing things only permitted their ‘way’. This creates a false standard in what rope bondage means, with what’s understood in Japan being ignored and shunned to promote pernicious, limiting teaching.

I come from a time when you kept your kink hidden for fear of arrest, or at least disgrace, and I meet many of my generation in Japan who say things like, “I miss the Shōwa–era bondage” (pre–1989). My understanding is a loss of the simplicity of motive from a time when it was still about the play and the interaction with the partner. Not about the damned rope, the styles of others, or the labels; Brands or faux lineages.

The past 40 years of rampant neoliberalism has had an adverse effect on the world. The Internet and Social Media can bring out the worst in people – they feel entitled, they want to be celebrities; influencers, showing off to an audience, rather than understanding the secrets only perceptible by the players. With it, they warp truth and facts for their own ends, and if we’re not careful, they could be lost forever.

Ugo: I found many interesting points in Sin’s answer. Responding to all might diffuse our discussion, so I’d like to focus on the topic of commercialism.

I‘m not a so–called bondage master. I founded SMpedia in 2009, a Wiki–like website focusing on Japanese SM culture in which I have been collecting and organizing historical references. Privately, I enjoy rope bondage, but don’t teach. I wish the information I collect may help us advance our discussion. My knowledge on the current scene in the West is limited, and I look forward to learning about this from the debate.

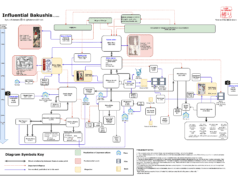

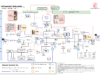

Articles on SMpedia are categorized: Kinbakushi, Artists, Photographers, etc. One is called Shikake–nin – instigators who made a significant contribution to the development of SM culture. Behind the scenes, their names are often not known. I understand commercialism played a pivotal role in the evolution of SM culture. Therefore, Shikake–nin were often business people, but not SM enthusiasts.

We had a magazine called Kitan Club (like Bizarre in the West) from 1947 to 1975 that greatly contributed to the expansion of SM culture in Japan. It was published by Yoshida Minoru. There’s little information, and no reference suggesting he was an SM enthusiast. He was said to be a market player and began Kitan Club in 1947 as an entertainment magazine. It nearly folded around 1952, but survived after Yoshida invited Minomura Kou to become editor, and it changed to an SM magazine. Presumably, he continued to publish Kitan Club as his business, going on to achieve moderate success.

Japan entered a golden era of SM in the 1970s, when tremendous amounts of SM magazines were launched. Interestingly, they were sold in ordinary bookstores, which contrasts to Kitan Club being only available in limited bookstores. One Shikake–nin of this boom was an editor named Miyasaka Shin. Previously only read by perverts, he dragged the kink magazine into the open. He believed that the society of the day could accept SM as a sexual urge, and published a succession of magazines such as SM Select, SM Collector and SM Kitan. Again, there’s no evidence to suggest he was an enthusiast, but only interested in SM as profitable publishing. Nureki was an editor and writer using various pen names before this magazine boom. The name Nureki Chimuo as a Kinbakushi emerged in 1973, after he became involved in photo shoots for these magazines.

The 70s were a period of massive change for SM culture. Tamai Keiyu was another important Shikake–nin of this era. More of a theatrical artist than a businessman, he was interested only in the success of the theater company he ran, which required a lot of money. To get it, he realized that SM–oriented plays could grab the interest of an audience (true since Ito Seiu’s era). He brought Osada Eikichi, who’d been performing underground into the limelight. Tamai’s SM shows led to Sakurada Denjiro and then Akechi Denki. Again, he wasn’t an enthusiast, but knew the power of SM as a business.

Before the 70s, we were in ‘a time where you kept your kink hidden for fear of arrest, or at least disgrace’ as Sin describes. But our society then became somewhat more accepting of sexually deviant practices. What drove this transition is complex, but it’s interesting to note some of the key players weren’t SM enthusiasts, but businessmen. It’s my understanding that commercialism is important for the development of SM as a culture. I’m not particularly interested in whether that’s a good or a bad thing. The current commercialism noted by Sin could play a pivotal role in the evolution of SM in the long term.

I’m also one of those people who miss the Shōwa–era bondage, but I know the young people of today will one day be saying, “I miss the Reiwa–era bondage” (2019–). History has a way of repeating itself. So, about the question, “What would Nureki, Osada, and Akechi think of the state of rope bondage today?” I’m sure they might reply, “I miss the good old days!”

I’d note that Nureki, Osada and Akechi (also Ito and Minomura) weren’t good in business. Of course, they all had families and therefore had to earn money to some extent. But if they had to choose between money and no SM or SM and no money, they would definitely choose the latter. Sin fears about the rise of commercialism in the West, but I think it could open a new direction of SM culture. Anyhow, sooner or later the money and no SM people will disappear from the main stage of SM history.

Marc: As BeShibari, I’ve been active for almost 20 years in the Belgian and European scene. Although I have performed, shared my insights in workshops and own the venue Shibari Lounge in Antwerp, I don’t feel that I’m an expert in rope bondage, and certainly not a ‘Master’. The longer I explore, the more doors open, with new worlds unfolding that stimulate my creativity and make me realize there’s still so much to discover. I consider myself as lingering on the outskirts of the community. Out of a ‘live and let live’ philosophy, I try to provide a platform for rope bondage in all its diversity, without feeling the need to impose myself on the scene. Until now I’ve never publicly shared my views on Shibari, its evolution and the community. Contributing to a debate is new to me, and I agreed because I have concerns regarding the direction Shibari is taking. I hope by voicing my opinion it will raise awareness and help give rise to independent views and the creativity to develop a western approach to Shibari.

I was attracted after seeing images of rope bondage from Japan in a magazine called Le Photo during the 70’s. This interest continued, seeking Japanese SM–videos and studying pictures in underground SM magazines. More than 10 years of living a spiritual lifestyle and undertaking retreats in India couldn’t suppress my perversion. When SM bars opened in Belgium 20 years ago, we got the chance to indulge the sexual kinks we’d long been suppressing. Exploring my sadism and deviant sexual nature was not only liberating, but also thrilling. At last, I could tie and inflict pain on a person who wanted me to. I was doing things I fantasized about with a consenting partner in a small circle of likeminded people. Shibari and SM were still rock ‘n’ roll. We were oddballs, and in a sense proud of it.

Since I began, there’s been a shift in the place SM and rope bondage have in society due to a broader movement of sexual and gender emancipation. They are gradually becoming more uncovered and entering public entertainment and debate. With SM and especially rope taking this giant leap towards mainstream, Shibari itself has changed, becoming something different from what I originally found attractive: kinky, carefree and wild. Focus on play between two partners gave way to new–age and moderation towards technique. Just as globalization and commercialization has led to standardization in many aspects of our lives, so it’s led to uniformity in Shibari. Social Media censorship also contributes to creating content only fitting within a narrowly defined frame of acceptance.

This movement works both ways, as I will stress later: Shibari is becoming fashionable and more socially acceptable, but in order to be so, the intention of why we do rope and the nature of Shibari itself is changing.

Being a pioneer, this development made my life easier, growing from being a secretive pervert out of necessity into a more socially appreciated kinkster. But observing the majority of the rope scene today, I miss some of the excitement and primal thrills of the old days. It all tends to be so well mannered and almost all looks the same. There’s no loose screw. Everybody’s looking for acceptance. Where are the rebels? Where are all the perverts? Where are the Akechi’s of today? I miss color in this increasingly grey landscape.

To address the question “What do you believe has led to the current state”: In the West we don’t have the same cultural background in the use of rope as in Japan. Images we saw were exotic and captivating, and very little information was available. Without prior knowledge, we had to try to figure out how the techniques worked from blurry images in SM magazines and videos. Some of us jokingly called these a pixel knot, referring to the pictures often being so bad that if you enlarged them, a knot would be reduced to a number of pixels and basically undecipherable. We had to improvise and put in time and effort to discover basic techniques, and become good at using them. We had little or no access to moving images hence the focus on techniques and patterns instead of on interaction.

Ugo describes the rise of the Japanese SM scene as the merits of several perceptive and resourceful businessmen who, rightly so, saw a market. In the West, it was the SM–lovers and Shibarists themselves that stepped into the arena of commerce. Somewhat talented Shibarists showed their work in SM–clubs, where they’d attract others who were curious. Some started to teach, not so much to place themselves in the role of expert, but to share knowledge and gain a little compensation for the effort they’d put in.

With the arrival of the Internet, Shibarites started getting global attention and fame. In the West we lack the culture of paying to go to an SM performance. A Shibarite would sometimes be invited to embellish a fetish event, but could hardly make money with it. Performing was financially unrewarding, so the accent for early professionals who aspired to make a living shifted to giving classes or selling rope and other materials.

Simultaneously, the Internet also led to lots of ‘free’ information on bondage. Many enthusiasts declared themselves ‘Masters’ and began teaching with little basic knowledge, and hardly any experience. Building a name and making money with your kink is appealing. Soon a spirit of competition arose between Shibarite to attract students.

To encourage people to take classes and learn to safely practice rope, the focus shifted towards addressing and tackling the risks by promoting anatomical study, stretching, and using only well–defined patterns. For many, these easy–to–copy patterns make up Japanese Shibari and learning these prefabricated ties gives them a tool to impress their partner, friends and peers in clubs. Many westerners also look up to Japanese forms of aesthetics and the pursuit of perfection. It works both ways!

Knowledge is an important commodity in the West. In Europe, life–long learning is considered a societal achievement: you need to be willing to continuously enrich your set of skills, adding to your toolbox, not just on a professional level, but also in hobbies, sports or even fetishes. To say you’ve acquired such–and–such skills from so–and–so teachers is considered a mark of confidence. Following the urge to ‘do’ or ‘be’ Japanese, people readily have other westerners tell them what’s actually Japanese. History, lineage and Hojōjutsu are dragged into the game to lift rope bondage from taboo, make it nobler and give it a sense of being an ancient discipline.

The mysterious idea that Shibari is only passed from master to student fits snugly within the western image of Japan being all about Zen Buddhism and martial arts. Japanese Shibarite have suddenly become masters and grandmasters. Ryūs are established to offer in–depth study of a certain lineage and a particular master’s take on Shibari. This has led to a better understanding of technique, but a side effect is patterns and styles being claimed, named after the ‘masters’ and ‘trademarked’. Students are imposed to follow a style, sometimes with the Ryū issuing a certificate or grading to measure levels of skill one can reach. In order to protect the Ryū’s ‘authenticity’ only people appointed by the ‘master’ or the ‘Deshi’ are allowed to teach. Every other creative rope twist is regarded as straying from the style. A few years ago, it came to the point that Shibarists were warning students that rigger X or Y was dangerous because they lacked appropriate certification to perform certain ties.

My opinion differs from Sin’s when it comes to ‘just’ teaching technique and dealing with risk management. Workshops setting out to have a full experience together become more and more available. However, exploring emotional interactions between two partners in these Ryū–style workshops have a risk of attempting to fit emotional response into the style taught.

It’s not my prerogative to say if the Ryū approach is correct. It certainly proves successful in Europe. Having an impatient mind, always on the lookout for something new, it’s hard for me to see most people practicing rope bondage nowadays more or less doing the same. Individuality and creativity have given way to adherence to a certain style resulting in a copy of a copy of a copy, ad infinitum.

Japanese words and concepts are used, not completely superfluously, but often to enhance a sense of mystery, feeding the necessity to follow workshops to uncover secrets in concepts like Zen, wabi–sabi or Ma (time; pause/space). Deepening one’s insight into certain aspects of Japanese culture is profoundly interesting, but not absolutely required to do rope bondage.

Niches have been created combining rope bondage with yoga, healing, Tantra, meditation or dance. Addressing the current hype of self–exploration through esoterism, body awareness and oriental spiritualism, people now start rope bondage to ‘go on an inner journey’ and of course, there are workshops to teach you how to do just that.

Artists, designers and critics have played a major role in the gradual acceptance of Shibari into mainstream society. They were the first to accept it into art and fashion, and Shibari is either considered to be an artform, or at least perceived as a craft interesting to art. With increasing frequency, we see crossovers from kink to avantgarde and ultimately pop culture. Collaborations with photographers, fashion designers, video artists and art schools, etc., have led to interesting fusion projects. The aesthetics in using rope on a human body also inspired many to edge a little bondage into their work. Some pioneers saw art as an opening to make rope bondage visible to a non–kink audience. The Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp have invited me to perform on several occasions and photographs of Wykd Dave’s work have been exhibited in The Louvre, Paris.

Emancipation and gender equality also made its mark on rope bondage and how it is taught. Empowerment causes women to take a place equal to men, not wanting to be a victim anymore, but an active partner in a Shibari session. The past image of women letting themselves be tortured and sexually abused is contradictory to the yoga–like trends one sees today.

Driven by prudishness, Social Media banning nudity and explicit content means that hardcore images of rope bondage can no longer be spread through public platforms. Therefore, they no longer contribute to a Shibarite’s fame. The need to be visible on the Internet to reach an audience feeds the trend to present Shibari as a sport practiced in a yoga outfit. Original focus: sadism, physical and emotional domination, erotic exhibition and play become diluted to make it acceptable and saleable to a larger market.

All this makes the community stray from the original game. To me, it’s all good so long as we’re all enjoying ourselves and respecting our differences. When spokespersons in the community start targeting others or dismissing them altogether, taking on a protectionist attitude, and telling others what is correct or even inventing stuff to impress their followers, the community loses its freedom, diversity and originality.

As mentioned in my introduction: I miss the rock ‘n’ roll attitude with which it all started. Nureki, Osada and Akechi might be very surprised to see the boom and how technically advanced it has become. I concur with Ugo and Sin that possibly they’d remark with sadness of missing the ‘old days’ and the perverted spirit. Luckily there’s still a strong undercurrent of independent souls willing to research multiple sources and mindsets to incorporate in creating their own styles. When we participated in Onawa Asobi 2019, with its array of diverse and highly creative performances, we saw this spirit is still very much alive in Japan. Fortunately, we see a strong undercurrent of independent souls in Europe willing to research multiple sources and mindsets to incorporate into creating their own styles.

As for the future: rope bondage is still more taboo than we think, and it will probably never be fully accepted. In the near future, Shibari will root itself in society as an adult subculture with one or more venues in every mid–sized to large town. The hype will slowly wane, and for a large part of the Shibari–seeking population, a ‘softer’ version will take hold. But there will always be deeper layers, and a more underground scene in which a select audience will indulge in the ‘hardcore’ stuff.

Rope bondage and the community are still evolving, and will continue to do so for a long time yet. I predict that a western style of Japanese–inspired Shibari will become manifest. In turn, the Japanese may become intrigued by western influences and ultimately, may choose to integrate some into the exploration of their own fetishes.

Again, this works both ways: we as pioneers should be delighted there’s so much interest, for this has made it easier for us to live our kinks. I am convinced the undercurrent is strong enough to see that not too much water is added to the wine. To end with the words of a well–respected member of the community both in Asia and the West, Yoi Yoshida, “Let’s not take it too seriously. We’re all just having fun.”

SM Select was first published at the end of 1970 by Tokyo Sansei–sya. General editor Miyasaka Shin prepared the launch with the help of Minomura Kou. In 1971, some Tokyo Sansei-sya editors founded their own company and started SM Fun. In 1972, Miyasaka founded his own publishing company and launched SM Collector, entering the era of the SM Magazine boom.

S&M Ab-hunter, SM Kitan, SM King, SM Gallery, SM Club, S&M Collector, S&M Sniper, SM Special, SM Sekai, SM Select, SM Tanki Club, SM Top, SM Hi–no–techo, SM Fan, SM Fantasia, SM Frontier, SM Play among others were published in the 70s. Nureki was involved in many of these magazines as Kinbakushi and rapidly evolved his Kinbaku during the boom.