In the second part of the virtual discussion with Ugo san of SMpedia, Marc BeShibari and Sin, I asked them more about their perspectives and appraisals.

You all bring up valid and interesting observations that many who’ve been around the evolution of rope bondage during the past thirty years might be hesitant to share.

As someone relatively new, I can confirm when I began my rope journey, I clearly saw the commercialized, structured approach focusing on technique over originality, and moving away from SM towards more sanitized forms.

The powerful influence of Social Media and marketing are accelerating the transformation as you describe. The COVID crisis has moved almost all rope bondage related activity online, removing the interpersonal element with even more emphasis on the technical aspects.

Will this lead to the end of SM related rope bondage as we know it? What can be done to restore individuality, the focus on the person being tied, and SM play under these conditions?

Sin: Yes, the Internet and Social Media are massive influences, not only proving material examples and opinion, but also endangering realities by replacing them with hypothesis, which then tends to snowball. Take Wikipedia, where much of its content is dubious, yet many innocently believe it as absolute gospel.

In my formative years, we didn’t have access to pretty much anything sexual, and especially not kinky. There was no scene, and Draconian laws in the UK made obtaining any material highly risky. There was a real hunger to discover, countered by a fear of being caught and exposed. With the Internet, it became improbable to regulate effectively, and there’s subsequently been an explosion of content. I really feel for younger generations today who now have the noise of information overload. It must be very challenging to decipher, and we see it in attitudes to sexual encounters where consumption cannot discern, and actually believes things like pornographic acting can be transposed to the bedroom. I imagine so many unsatisfied casualties.

Ugo’s statement about Japanese society becoming accepting of kink four decades ahead of the West is significant. While we remained largely underground, Japan had a head start, and thus became the go–to resource. They matured while we were still in our infancy.

Rightly or wrongly, catalysts such as 50 Shades opened a floodgate of interest towards a huge increase in BDSM participation, and as society became more accepting of adult pursuits, traditional stigma lessened. It has been suggested that those who indulge in BDSM may be better off psychologically. However, as a practice, rope with the sadomasochistic and erotic excluded can be fairly innocuous. But with growth comes greater numbers with personal issues, possibly prevalent in the sub–field of rope bondage. We encounter individuals with signs of bi–polar and borderline autistic–Asperger conditions notably enjoying narrow doctrines and repetitive tying. Therefore, rope bondage could be considered therapeutic, not only for those enjoying being inside the rope, but also those using it as a means to connect with the gender of their preference. It is possible that by disguising inescapable intimacy as martial art, etc., it also provides convenience to some in their rationale, despite the ties having little comparison to Hojōjutsu bindings because they’re not aiming to maim or kill.

Marc laments a lack of individuality, and generally, I would agree. My personal philosophy struggles to comprehend why anyone would wish to regiment something as intimate and personal as applying rope to another person. So, naturally, I wrestle with irrational concepts attempting to homogenize tying. But I do come across more and more people following their hearts, and enjoying their predilections with their partners. Sadly, I still note some following somebody else’s product, and as Marc describes, easy–to–copy patterns and prefabricated ties, much to the noticeable reported frustration of more evolved bottoming partners.

I’ve never seriously taught. Instead, I like to encourage individuals to find their own paths, principally by conversation, where I make myself approachable, and am always inspired in return by the interaction. A woman may empower me to be whatever she desires, but I don’t use terms like Master. I attended a workshop once, but didn’t return for the second day because frankly, I found it utterly ridiculous, realizing the instructor was running far ahead of his actual understanding. I was once invited to hold a workshop, but after meticulously explaining how the psychological–emotional functioned, while the ladies instinctively understood, some of the guys still bemoaned they hadn’t learned a new tie. So, I just gave up.

My focus is always the female bottom perspective, because that’s who I work with, especially sophisticated ladies who understand what they desire from restraint in rope. Their observations are highly valuable and educational. Over the years I’ve absorbed rope play in pink theatres, SM and Happening bars, commonly accompanied by a lady. As in the West, I will always ask about their first steps into rope bondage, because in part, I’m seeking their personal narrative to work from. Common appraisals of witnessing tying, mostly recorded, some live, return apathy to ‘big names’. They’re not interested in schools or styles. They want something for themselves, and when they find a thing that piques their libido, I take note and try to understand how it could function to our mutual advantage.

Having friends and communicating with a range of practitioners in Japan, I admit what’s printed in articles is the tip of an iceberg. Behind edits, from long–term contacts, is a pool of corroboration establishing a picture very different from most interpretations in the West.

In Japan, I’m often asked why they don’t see deviant erotic–SM in the West. I used to chastise them for giving a false; diluted image and not fully demonstrating their kinks, until Tesshin experienced a spectator in Europe calling the police as he used a whip. Thus, we see how Vanilla influence and litigation culture are also having weakening effects.

Maybe it’s a double–edged sword, and I’m a dying breed. What’s intrinsically Japanese is being erased from western Japanese Bondage because it’s all too perverted for most western tastes. As Akechi once alluded, rope bondage is best kept underground, and if the SM goes that way, perhaps it’s for the better. Maybe the private, subterranean scene I enjoy will flourish in secret, best away from riggers with ostentatious exposé.

I lament that commercialism, societal pressure and laws may undoubtedly redefine rope bondage, but much of this tsunami of interest is at least teaching the basic technical aspects. As Yukimura, and others later said, “Rope is free” – ultimately, you have to get away from anybody else’s style to be credible.

I’ll push ever onward with my own discoveries, evolution and enjoyment and, if I can be of service, help those who aspire to advance beyond the macramé. At my age, I’m very comfortable walking in my shoes. However, while I still enjoy private sessions, including with paying lady clients, the COVID–19 crisis has sadly halted all underground epicurean event work, where I do live hardcore Kinbaku sessions demanding to be absolutely believable for this sort of discerning audience. They’re not interested in who I may be or, for that matter, the technical nature of the tying, but in the authenticity of what they’re observing.

I would imagine that the pandemic has sadly removed many possibilities for most practitioners to pursue progression. This has significantly limited exposure to a wave of remote media unfortunately even further detached from reality in a quest for many to survive financially, or just to be another passenger on, now a very, very long bandwagon.

Marc: As Shibari seeps popular into the mainstream, the audience it attracts becomes larger and more diverse. It’s not the original SM and erotic approach that necessarily appeals to these newcomers, and many may feel more affinity with the modern, cleaner ‘new age’ kind of rope play. Some may not even be aware its origins are related to SM.

People like me feel some of the original attraction is lacking. However, I’m convinced we don’t have to fear individuality will be lost and SM rope play as we know it will end. Plenty of newcomers still start their explorations into the rope scene because they’re looking for something kinky to provide the thrill of sexiness, excitement and ‘living on the edge’. Initially they may be intimidated by the safety instructions and ‘the right way to do Shibari’ propagated in so many workshops. At the same time, they will also be confronted with the prudish censorship on Social Media, which helps create a false image of what Japanese rope bondage is originally about. After passing the more easily accessible and often rigid technical and aesthetic approaches, some will want to dig deeper and explore their individual creativity. They may discover and venture onto the paths of more free-spirited or erotic styles of rope bondage.

I look at this development like the swing of a pendulum: from the original sado–erotic Shibari practiced by a largely hidden scene, in this #MeToo era it now swings towards a rather sanitized kind of rope play which makes the community timid and over–regulated. A school style approach to learning stimulates this movement, offering a framework in which to practice without overstepping boundaries. We notice the already discussed Ryū–mentality combined with the need for peer approval enhances a certain degree of standardization in the West. This standardization I never recognized in the Japanese magazines and videos that inspired me, and in my humble opinion it does not have its origins in Japan.

When we participated in Onawa Asobi 2019, my partner Jess and I got to experience this ‘deep pool of cross–corroboration’ Sin mentioned in his response first hand. We were amazed by the free spirit and great diversity in the performances, going from pure SM via romantic to even hilariously funny. This sparked my belief there are deeper layers to Japanese SM many of us in the West haven’t yet begun to discover. What we perceive to be Japanese rope bondage is indeed only the tip of an iceberg.

Events like Onawa Asobi and Eurix create opportunities to practice individual styles and erotic play within acceptable borders. This can help make the pendulum swing back to where individuality, edge play and eroticism will come to blossom in western interpretations of Japanese rope bondage. If we welcome diversity and embrace both ends of the spectrum without losing our own identities and backgrounds, I believe we have a lot on offer.

Ugo: I enjoyed reading Marc’s analysis of the evolution and diversification of Kinbaku in the West. Personally, I believe we’re in a very exciting time as we see how it’s evolving into new forms after entering the western niche. Us Japanese could never imagine Yoga–Kinbaku. I don’t know if it will survive or not, but I respect the ingenuity of the people who came up with the idea. At the same time, I can understand Sin’s concerns about the negative aspects of such emerging forms of Kinbaku on the indigenous way we know. In my second reply, I’d like to present some history in Japan related to the terms ‘returning to SM’, ‘pendulum’ and ‘sanitization’.

Although there’s some overlap with my previous reply, let me summarize a brief history of Kinbaku culture in Japan, roughly divided into four phases:

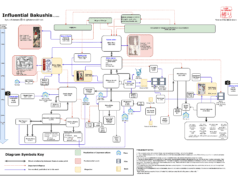

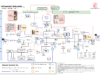

The Dawn Phase (1915–44): Kinbaku or SM culture in Japan has its origin with Ito Seiu (1882–1961). Ito started his Kinbaku in 1916, if not earlier, and published his Studies on Seme in 1928. In this era, it was essentially a morbid play for crazy people. Ito was often introduced as a nutty man in mass–circulation magazines despite his fame as an artist, theater critic, etc. His Kinbaku was greatly influenced by Kabuki plays, in which princesses, princes or bad guys were often bound. Even in Japanese articles, you may find some that attribute the origins to Hojōjutsu. These are based on false observations. Kinbaku culture in Japan has its roots in theater. But it’s true many modern Kinbakushi subsequently researched Hojōjutsu and incorporated some technique into their Shibari.

Growth (1945–69): Kitan Club was launched in 1947 and after Minomura became editor in 1952 it started to focus on minor sexual predilections such as Kinbaku, Seppuku, homosexuality, scatology, etc. Although not a general magazine, it continued until 1975 and nurtured Japanese kink culture. Nureki was one of its writers. The climate of Kinbaku being a forbidden play continued, and enthusiasts understood once their sexual predilections were known, they could be instantly kicked out of society.

Note the term ‘SM’ was not yet in general usage. The equivalent word was Seme, used since Ito Seiu, and meant the actions of tying someone with ropes and, in some cases, hitting someone by bamboo, etc. I’m not sure what the English equivalent would be. The word ‘torture’ is often used, but I feel uneasy with this translation. Also, please note that Ito used the word Kinbaku, but used it more as a categorical term for a theatrical motif. In Kitan Club, the word Kinbaku was used as we use it now.

Maturation (1970–90): as mentioned, underground taboos associated with the global counterculture movement gradually came to the forefront around 1970. It was during this period that the term SM became widespread. Available in general bookstores, SM magazines (SM Select, SM Fan, SM Collector, etc.) were launched one after the other, and the term SM was used in TV programs. I believe what Marc and Sin think of as ‘SM’ is from this era. The term reminds Japanese people now in their 50s and older of rope and leather bondage, whips, wax, enemas and vibrators. These themes were frequently used in SM magazines, shows, films and videos of this era. Osada probably didn’t do enemas, but Akechi was anally fixated, and his SM shows incorporated wax play, enemas and vibrators.

In this era, the struggle between those claiming freedom of expression and those protecting public decency made evolution dynamic, and various SM and erotic cultures emerged. At a certain time, authority control became tighter, which altered new forms of SM play, and at other times, regulation became more relaxed. This is as Marc describes as a ‘pendulum’ state in the West today.

Around 1970, the community’s advocacy for freedom of expression was strong, and SM was featured in general TV shows. In hindsight, we were probably out of line. I don’t want my children to watch SM plays on TV, and our current broadcast codes are much stricter. Consequently, the contents of today’s SM plays have to be sanitized so more people can accept them, just as we now see in the West.

Therefore, rope bondage has a better chance to endure than the whipping, waxing, enemas and vibrators, etc. Kinbaku has aspects of art, evidenced by its use in traditional Kabuki and Bunraku, as well as in its craftsmanship. In 1989, Akechi appeared on a general TV quiz program in which participants guessed his craft by asking questions. The correct answer was, “I’m a Kinbakushi”, and he demonstrated his Kikkou–shibari on a clothed lady to applause.

The term Kinbakushi appeared in Kitan Club by 1970. However, its usage wasn’t widespread until the end of the 90s, which reflects the fact people didn’t care who tied the models. In the mid 70s, some enthusiasts started to be aware of the Kinbakushi and the photographer, and in the late 90s or early 2000s Kinbakushi gathered attention among the general public. From the 90s, we start to find SM videos in which the term Kinbaku Masters are first highlighted.

The 90s was the period these Kinbaku Masters were brought into the limelight, and the center of this boom was Akechi. SM magazines and videos had already started to follow a path to extinction. Therefore, he had to seek a place for his activities, mostly with on–stage performances instead of in magazines or videos.

Inclusion (1990–present): the decline of SM magazines and videos probably came about because of the rise of the Internet. In the late 80s, services such as Nifty started as a text–based telecommunication, and in the early 90s NCSA Mosaic, the ancestor of today’s web browser. In the late 90s this innovative technology spread rapidly, and people with similar interests started exchanging information. kikkou.com was founded in 1996 by an editor of SM magazines. The website provided information of the Japanese SM scene in English, boosting the spread abroad. Early information contained ‘How-to’ Shibari lectures of Shima Shikou and Randa Mai. Osada Steve purchased kikkou.com in 2001 and continued to introduce Japanese Kinbaku Masters abroad.

People with similar interests who’d previously interacted in virtual conference rooms began to meet to exchange information at what we called Offukai (off–Internet face–to–face gatherings), including those interested in Kinbaku. Basically, they were amateur. The passive audiences of the 70s and 80s became practitioners, and an era of inclusion began – anybody could be a Kinbakushi. I’m sure similar movements occurred in the West, and some people started to incorporate Japanese–style rope techniques via the Internet.

During this time, various paths were paved to learn tying. For instance, Randa Mai published a series of well–organized How–to–Kinbaku books in 1997. Not only from DVDs or textbooks, people could now learn skills in various places. We have a style of sexual bar, called a Happening Bar, a place where people having various sexual orientations, such as SM, cross–dressing, exhibitionism, etc. gather and enjoy conversation and spontaneous acts. Customers are allowed to play, and Kinbaku enthusiasts try to improve their tying. Some talented people started to give classes in these bars, and many of the current masters in Japan are associated with them. Of course, some distinguished Kinbakushi now run their own schools or provide private lessons.

As for the Dojō–style school, which seems to have grown in popularity in the West, there’s the Bakuyukai in Tokyo. Initially established in 1996 by Miura Takumi, its rigorous formulations you might see in a western Dojō. Although Sin has a negative view of the system, it does have positive aspects. Japanese culture tends to give importance to mastering repeated simple exercises prior to acting intuitively. Strict rules may be needed to maintain integrity. The Bakuyukai produced many good Kinbakushi, which shows the system working. But I have to remind you this is not the only place where we can learn. Indeed, no other big Dojō became successful, and there are many other ways to learn than the ones mentioned.

To conclude, I’d like to add a characteristic change that occurred during this period – the formation of a network of rope meetings. There’s no clear definition of what a Nawakai is, but my definition is a gathering for amateur enthusiasts, most of whose bondage skills are quite high. It’s similar to the Offukai, and in fact, some evolved into Nawakai, also called Salon, Circle, Lounge, Benkyoukai (study group), Kouryuukai (networking party), Nawadokoro (rope place), etc.

Previously, we had similar gatherings sporadically emerging with lecture–styles from so–called professionals. A tremendous number of Nawakai emerged in the 2000s, many organized by amateur enthusiasts that had already obtained a certain level of skills from various sources. Especially in the big cities, there were many different ones that started to interact and formed a network. Once formed, positive feedback instantly evolved the skills of the participants, leading to the explosion in the diversity of Kinbaku in Japan.

I attended one in 2010 called Chika–shitsu (a double meaning: abashment and cellar). Interestingly, the organizer was Miura, who also ran the rigorous Dojō–styled Bakuyukai. In the homepage he wrote, “The reason for starting Chika–shitsu was to promote erotic activities, mainly SM, in the old style. I am hoping that we can go back to the beginning and find a new style.” This reminds me of Sin’s hopes for ‘returning to SM’.

Participating at the first Chika–shitsu meeting, I was shocked to see the Kinbaku of Ero Ouji. That was my first time, and I didn’t even know his name. Yet, he was such a great Kinbakushi. I note there are so many great amateurs and therefore, not so well known in public as the so–called professionals.

I believe the crucial point of the network of Nawakai that formed during this era, is that most participants already had certain skills when they started, because they’d been educating themselves in various ways. They were attending many different Nawakai, influencing each other and evolving their own styles by incorporating tips from others. These activities quickly raised the bar. Although not explicitly defined, the basic etiquette of a Nawakai is to value diversity and encourage each other by freely imparting knowledge. I think Yoi Yoshida, who Marc invited to Antwerp, is one of the main protagonists of the network of Nawakai activities. I can imagine Marc’s Shibari Lounge has such an atmosphere.

Maybe Nawakai is the extreme opposite of the Dojō style, but both have their attributes. Nobody can tell which is better. As Miura did, we may take positives from both styles and, of course, we can stick to one style when it fits the individual.

Here are my short answers to the other questions:

“Will this lead to the end of SM related rope bondage as we know it?” Yes, the SM we know will end as it did in the past. SM culture keeps evolving and changing.

“What can be done to restore individuality, the focus on the person being tied, and SM play under these conditions?” Each person should have their own sadomasochism. So, what we should do is just do what we want to do. And, I believe the change of the relationship between the person tying and the person being tied also contributed to the evolution of Kinbaku.