If you watch Japanese bondage videos, or have ever flipped through old Japanese SM magazines such as Kitan Club or Sun and Moon, you’ve most likely come across an image of a bound woman to whom a handwritten sign has been attached. These can be mystifying for Western viewers, particularly those who can’t read a word of Japanese. Whatever does the sign say? And why is it there?

Take, for example, the scene above, from the 2016 video “Kinbaku Kinema 2,” filmed and directed by Sugiura Norio and starring Wakabayashi Miho with bondage by Naka Akira. As you can see, a woman in a kimono has been perched atop a school desk with arms bound behind her back and legs widely spread and bound. Just beneath her bottom, taped to the desk, is a handwritten sign. It reads 万引少女のお母さん (manbiki shojo no okaasan, which means “mother of a shoplifting girl”). If I were asked to rewrite the sign for English speakers, I’d print in big, bold letters: THIS WOMAN RAISED A SHOPLIFTER!! Clearly, the sign is intended to increase the woman’s shame as she is tied out as punishment for her failings as a parent.

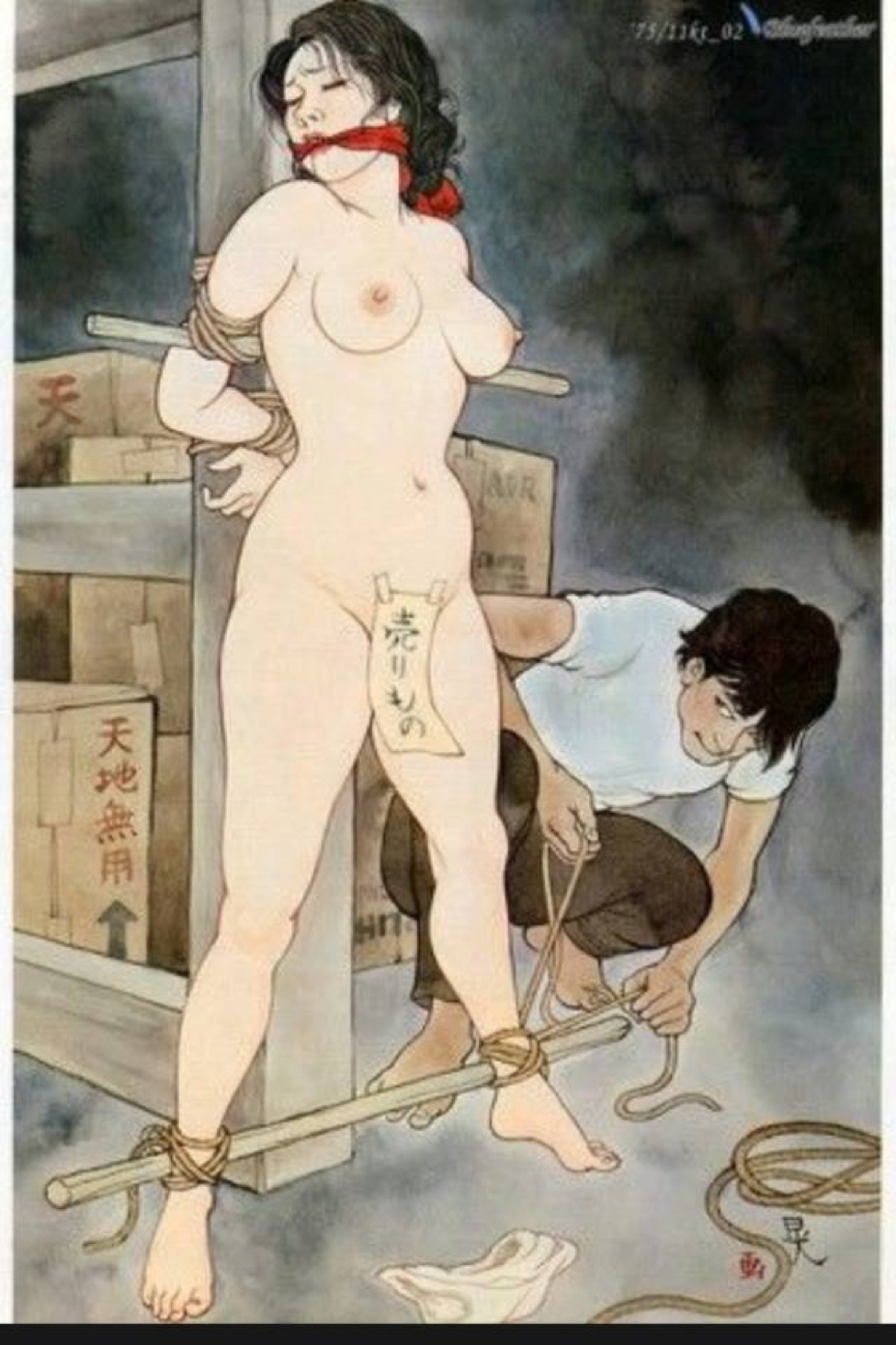

Here’s another example by famed bondage artist Minomura Kou (real name Suma Toshiyuki (1920-2000), who also drew under the name Kita Reiko). Here the strategically placed sign says 売り物 (urimono, meaning “object for sale.”)

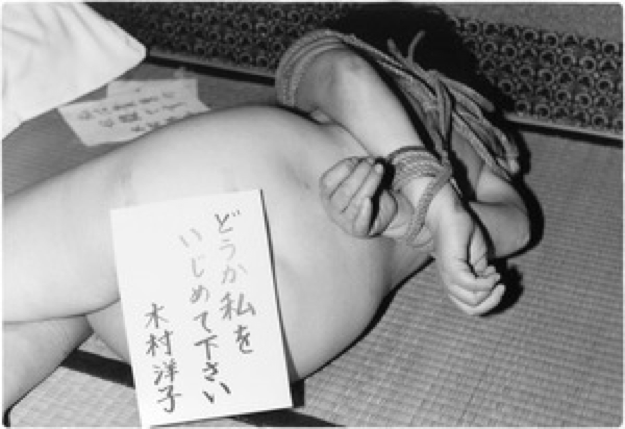

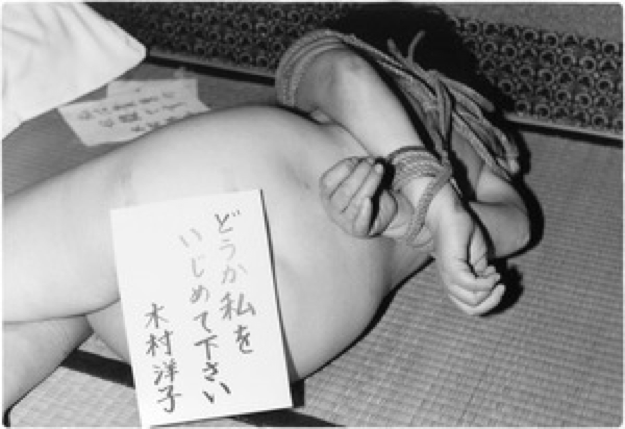

The black-and-white photograph below is an example of what are called 分譲写真 (bunjō shashin, “shared photos”), which from the 1950s on were sold as sets through advertisements in the back pages of Japanese SM magazines, most notably Kitan Club. Here, not only is the poor miss tied up but someone has pasted a sign to her behind. It reads どうか私をいじめてください。木村洋子(dōka watashi o ijimete kudasai. Kimura Yoko). I’ll translate that as, “Would someone please be so kind as to abuse me? (Signed,) Kimura Yoko.”

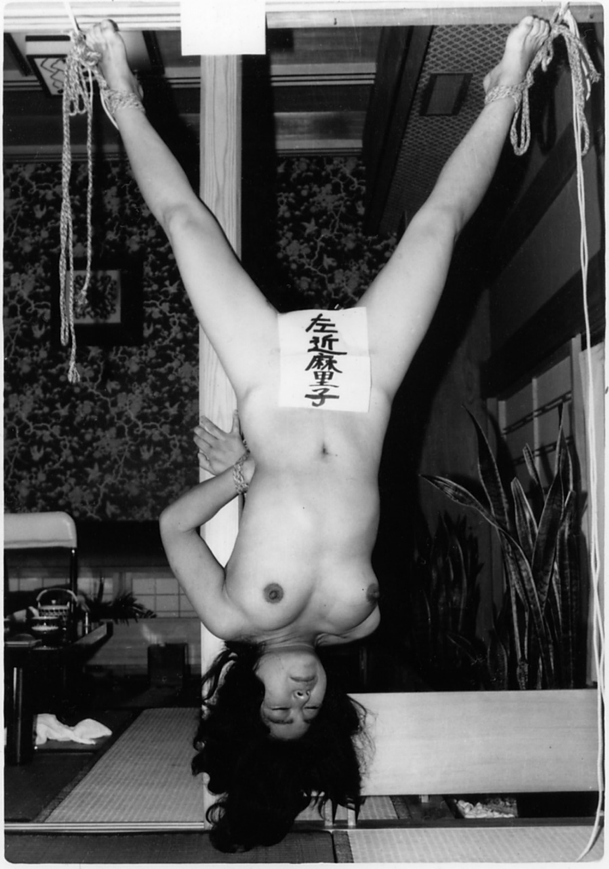

Below, another example of a bondage photograph with, for lack of a better word, I like to call a “sign of shame.” (As far as I have been able to determine, there’s no specific term for such signs in Japanese.) In this one we see a woman suspended upside down with legs widely spread. A handwritten sign, carefully positioned to completely covers her crotch, reads 左近麻里子 (Sakin Mariko). This is the nom de plume of the model, who was quite a famous at the time. (The rope work may be by 山本一章 (Yamamoto Kazuaki), who did a lot of upside-down suspensions like this. Sakin Mariko was featured in his column in Kitan Club in 1967, so they obviously worked together.) This photo was lent by a Japanese man in his 60s, who explained that a Japanese woman of that era would be extremely embarrassed to be seen without clothes. To have her name broadcast to the world while naked would be far worse, he said, so the photograph is a wonderful expression of Japanese ideas of shame.

It is important to acknowledge that these last three images were made and disseminated at a time when magazines were strictly forbidden from showing or depicting the genitals. This censorship was taken seriously, and it was not uncommon for an editor or publisher who skirted the law to be hauled down to a police station or even jailed. In such an environment, these strategically placed signs were obviously a useful tool in bondage photography: they concealed the forbidden parts without ruining the mood of the photograph. In fact, they very nicely added to the story and drama. But it would be a mistake to dismiss such signs as a modern expediency, or a mere trick to get around censorship. Because there is a clear link to shame and punishment in earlier times.

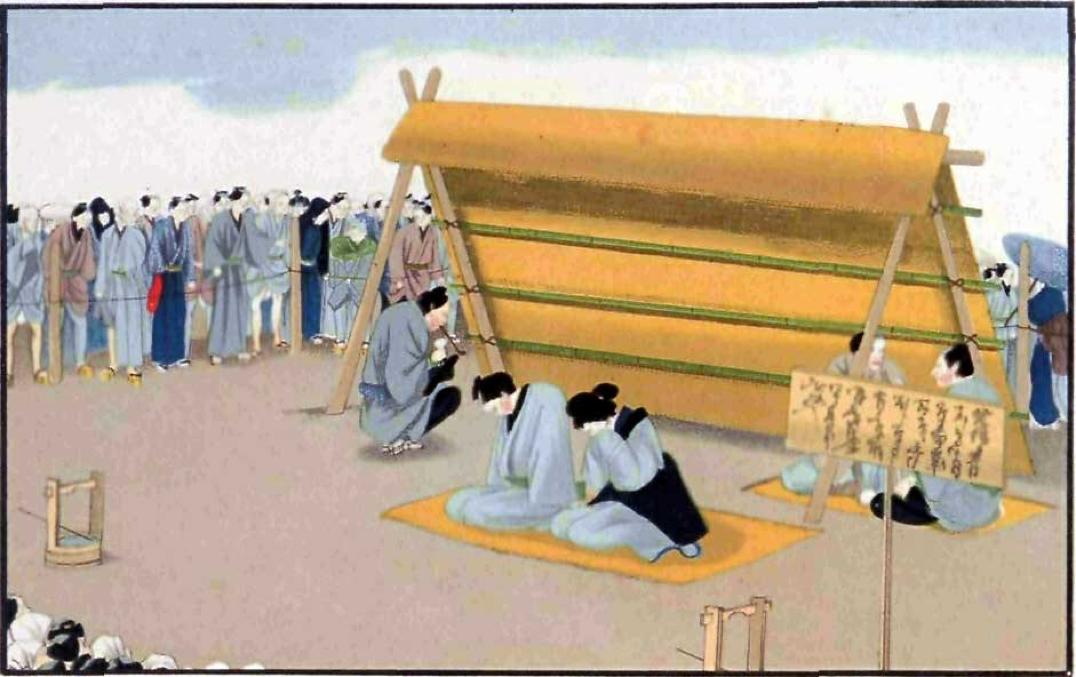

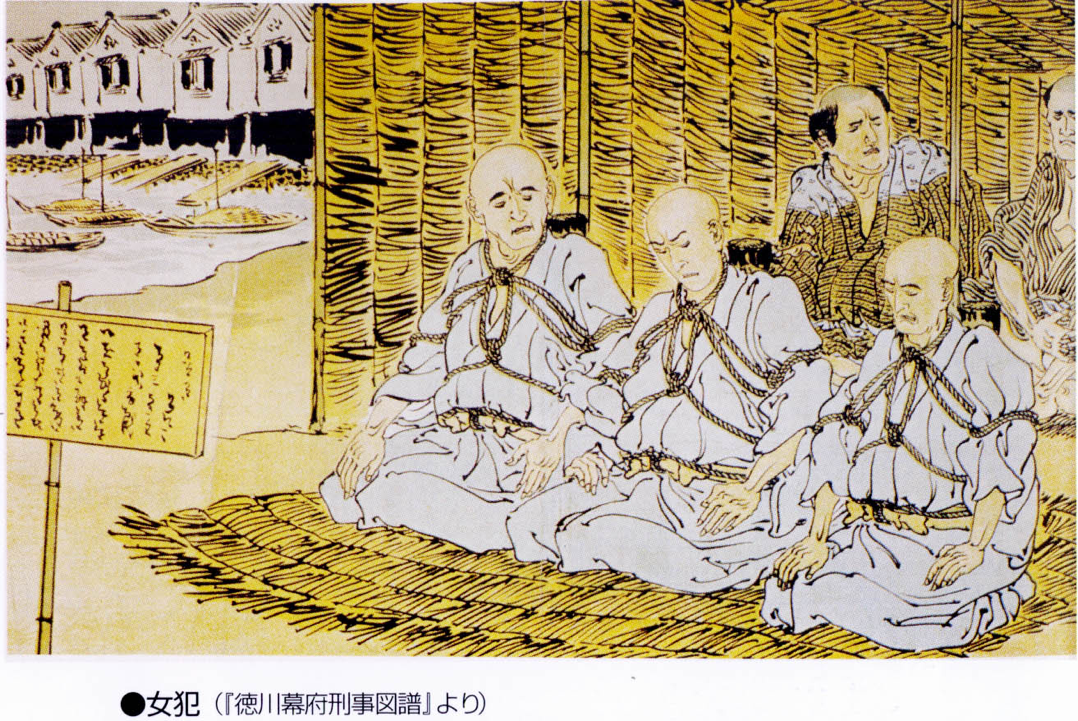

Look, for example, as this illustration from a famous book that details crime and punishment during the Edo Period,(徳川幕府刑罰図譜 Tokugawa bakufu keiji zufu, which was published in 1878. It shows three monks being shamed in public as punishment for licentious behavior with women. They have been positioned on mats in an outdoor place with many passersby, tied with rope around their upper bodies. (The ties are obviously more for show and emotional effect than restraint, obviously; it was very shameful to be tied up in those days in Japan.) But what I would most like you to notice is the sign posted to their left, which details their offenses for all the world to see.

A similar scene was observed by J.M.W. Silver, a Western visitor to Japan, and published in London in 1867 in his book Sketches of Japanese Manners and Customs. Here, a couple have been sentenced for adultery to public exposure. Their sentence, and the details are their wrongdoings, are written on the sign behind them.